Alfons Mucha: Czech king of the Art Nouveau

By Tracy A. Burns

The prolific Mucha

The imaginative and passionate creations by legendary Art Nouveau painter and decorative artist Alphonse Mucha are well-known throughout the world, especially the idealized images of Sarah Bernhardt with her poignant, exhilarating gaze. An avid supporter of democratic Czechoslovakia, Mucha is also celebrated for his patriotic and folk art themes that celebrate not only the Czechoslovak nation but also Slav unity. He was certainly prolific, creating posters, books, magazine and book illustrations, stained glass windows, jewelry, theatre sets, costumes, and more. But Mucha had not always been in the limelight. His big break did not come until he was 35 years old.

The imaginative and passionate creations by legendary Art Nouveau painter and decorative artist Alphonse Mucha are well-known throughout the world, especially the idealized images of Sarah Bernhardt with her poignant, exhilarating gaze. An avid supporter of democratic Czechoslovakia, Mucha is also celebrated for his patriotic and folk art themes that celebrate not only the Czechoslovak nation but also Slav unity. He was certainly prolific, creating posters, books, magazine and book illustrations, stained glass windows, jewelry, theatre sets, costumes, and more. But Mucha had not always been in the limelight. His big break did not come until he was 35 years old.

July 24, 1860, and childhood

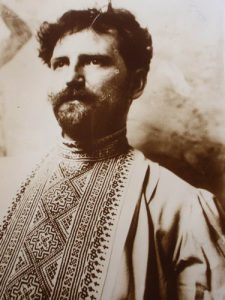

Alphonse Mucha came into the world July 24, 1860 in Ivančice, south Moravia. His father, Andreas Mucha, worked as a court usher while his very religious mother, Amálie, served as a governess in Vienna, Austria. He had two half-sisters from his father’s previous marriage and two younger sisters. Part of the building he called home was used for the town jail.

Under Austrian domination, the Czech lands were part of the Habsburg Empire where German was the official language, and there was virtually no Czech culture. Yet the decade Mucha was born into held some promise: those were the years of the Czech National Revival when Czech nationalists strove for autonomy and made efforts to revive Czech culture. Yet there were terrible times as well. In 1866, the decisive battle in the Prussian-Austrian war took place in Hradec Králové, 20 miles from Mucha’s village. As the Prussians triumphed, the youngster saw corpses being hurled into common graves near his home. Religion would play a part in Mucha’s life, too. At age 11 he joined a choir of a Catholic church in Brno. In 1872 he began attending secondary school in the Moravian capital but was expelled in 1877 due to poor academic performance.

From Vienna to Paris

Mucha found employment painting stage scenery for a Vienna-based theatre company in 1881. In 1882 his drawing of Count Karl Khuen-Belasi’s residence was so well-received that the Count financially supported the young artist during two years of study in Munich and continued to help him when he moved to Paris in 1887. When the financial aid stopped, Mucha had to give up his studies and take up work contributing to French and Czech publications, creating book illustrations, and teaching drawing. For a time he shared a studio with French Post-Impressionist artist Paul Gauguin, and he also met Swedish writer and painter August Strindberg, who encouraged him in spiritualism and occultism. Mucha also delved into photography.

Mucha’s big break and instant success

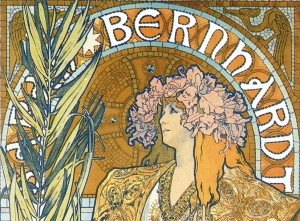

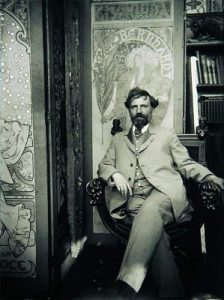

His big break came at the end of 1894 when he created a new lithographed poster for Sarah Bernhardt, advertising the production of Gismonda. Mucha got the job by accident, at the last minute, because all the other artists at Lemercier were on vacation. His style became the talk of the town. His unique poster featured a narrow, two-meter-high Sarah Bernhardt, portrayed with muted pastel colors. The poster was so popular that people armed with razors cut them off the hoardings at night. During 1985 the overnight sensation received a six-year contract with Sarah Bernhardt and was well on his way to stardom. The following year he agreed to make posters for the printer Champenois, who published Mucha’s creations on calendars, postcards, theatre programs, and menus. His work drew more international acclaim after the printer licensed his designs to companies and publications throughout Europe and North America. By 1897 Mucha was holding solo exhibitions. During the next two years, his creations would be shown in Vienna, Prague, Budapest, Munich, London, New York, and other cities.

His big break came at the end of 1894 when he created a new lithographed poster for Sarah Bernhardt, advertising the production of Gismonda. Mucha got the job by accident, at the last minute, because all the other artists at Lemercier were on vacation. His style became the talk of the town. His unique poster featured a narrow, two-meter-high Sarah Bernhardt, portrayed with muted pastel colors. The poster was so popular that people armed with razors cut them off the hoardings at night. During 1985 the overnight sensation received a six-year contract with Sarah Bernhardt and was well on his way to stardom. The following year he agreed to make posters for the printer Champenois, who published Mucha’s creations on calendars, postcards, theatre programs, and menus. His work drew more international acclaim after the printer licensed his designs to companies and publications throughout Europe and North America. By 1897 Mucha was holding solo exhibitions. During the next two years, his creations would be shown in Vienna, Prague, Budapest, Munich, London, New York, and other cities.

The Mucha style

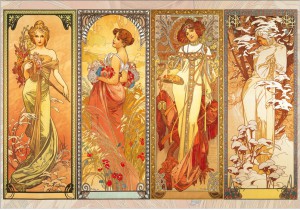

The Mucha style features beautiful, young women exuding optimism and happiness in extravagant, flowing robes designed in pale pastels. Flowers or crescent moons make halos around the bewitching figure’s head. Floral or botanic ornamentation also appears. Folk elements that are not only Czech but also Byzantine, Celtic, Rococo, Gothic and Judaic, among others, are characteristic, too. Arabesques plus strong, stylized outlines and naturalistic detail help capture the viewer’s admiration.

The Mucha style features beautiful, young women exuding optimism and happiness in extravagant, flowing robes designed in pale pastels. Flowers or crescent moons make halos around the bewitching figure’s head. Floral or botanic ornamentation also appears. Folk elements that are not only Czech but also Byzantine, Celtic, Rococo, Gothic and Judaic, among others, are characteristic, too. Arabesques plus strong, stylized outlines and naturalistic detail help capture the viewer’s admiration.

From Le Pater to Exposition Universalles

In 1899 Mucha wrote commentaries and designed the pictures of a book called Le Pater, his personal interpretation of the Lord’s Prayer in which he divides the prayer into seven verses and analyzes the verses in sets of three decorative pages. In 1900 his gripping and energizing art earned even more international praise when he created the décor for the Bosnia-Herzegovina Pavilion at the Exposition Universalles. Not only was he awarded the silver prize, but he also had the honor of becoming a knight of the Order of Franz Joseph I, in recognition of his contributions to the Habsburg realm.

In the USA

When Mucha traveled to the USA for the first time in 1904, the front page of The New York Daily News revered him as “the world’s greatest decorative artist.” The formerly poor book illustrator who never finished high school made two more trips to the USA, where he took up teaching positions. During a fourth trip he designed creations for wealthy American businessman Charles Richard Crane, who was enthralled by Slav nationalism and enthusiastic about Mucha’s idea for a series of paintings celebrating Slav history.

Starting a family

Between trips to the USA, in 1906, Mucha got married in Prague to Maruška Chytilová, his former student who was 22 years younger than he. Mucha moved back to Prague in 1910 with a one-year-old daughter, Jaroslava. His son Jiří would be born five years later. (Jiří would become a journalist, novelist, and screenwriter who fervently promoted his father’s works and wrote his biography. He would also be imprisoned by the Communists for a time as a spy.)

Several accomplishments: the Municipal House and Saint Vitus’ Cathedral

From 1910, when he moved back to Prague, Mucha’s vibrant murals and ceiling paintings adorned the Lord Mayor’s Hall in the Municipal House, illustrating the glorious history of the Czechs and the unity of the Slav nations. On the ceiling fresco, he even portrayed Czech historical personalities. After Czechoslovakia was established in 1918, Mucha became a fervent supporter of the newly-founded democracy and designed the country’s first postage stamps and banknotes. Years later, in 1931 he applied his brilliant skills to colorful, dynamic stained-glass windows in Prague’s Saint Vitus’ Cathedral, depicting Saint Wenceslas, the nation’s patron saint, as a child with his grandmother Saint Ludmila in a central panel surrounded by 36 other panels focusing on the lives of Saints Cyril and Methodius.

From 1910, when he moved back to Prague, Mucha’s vibrant murals and ceiling paintings adorned the Lord Mayor’s Hall in the Municipal House, illustrating the glorious history of the Czechs and the unity of the Slav nations. On the ceiling fresco, he even portrayed Czech historical personalities. After Czechoslovakia was established in 1918, Mucha became a fervent supporter of the newly-founded democracy and designed the country’s first postage stamps and banknotes. Years later, in 1931 he applied his brilliant skills to colorful, dynamic stained-glass windows in Prague’s Saint Vitus’ Cathedral, depicting Saint Wenceslas, the nation’s patron saint, as a child with his grandmother Saint Ludmila in a central panel surrounded by 36 other panels focusing on the lives of Saints Cyril and Methodius.

The Slav Epic

Mucha’s masterpiece, The Slav Epic, portrays the heroic history of the Czechs and Slavs and is especially notable for intertwining historical painting with symbolism. It was meant to inspire viewers in terms of integrity, bravery, and faith. Sponsored by Crane, Mucha began tackling the Slav Epic in 1900. Nine years later the first five canvases were exhibited at Prague’s Klementinum. When the exhibition traveled to Chicago, more than 53,000 enthusiastic fans came to see the monumental canvases in one week alone. From 1928 to 29 the Slav Epic paintings made an appearance at Prague’s Trade Fair Palace in honor of the 10th anniversary of the existence of Czechoslovakia.

Finishing the Slav Epic series

Finally, in 1930, Mucha completed the last Slav Epic creation – the 20th canvas in the series titled “The Apotheosis of the Slavs, Slavs for Humanity”. The vibrant painting celebrates the independence of the Slav nations. The canvas can be divided into four parts with a different color dominating each section that shows an era in Slav history. Dominating the foreground is a central bare-chested figure that stands for the dynamic, independent nation. A Christ figure lurking behind him acts as his protector. Other canvases in the series celebrate Czech historical figures such as educator Jan Amos Komenský, who was exiled from Bohemia for his beliefs and gained recognition as a spiritual leader.

Finally, in 1930, Mucha completed the last Slav Epic creation – the 20th canvas in the series titled “The Apotheosis of the Slavs, Slavs for Humanity”. The vibrant painting celebrates the independence of the Slav nations. The canvas can be divided into four parts with a different color dominating each section that shows an era in Slav history. Dominating the foreground is a central bare-chested figure that stands for the dynamic, independent nation. A Christ figure lurking behind him acts as his protector. Other canvases in the series celebrate Czech historical figures such as educator Jan Amos Komenský, who was exiled from Bohemia for his beliefs and gained recognition as a spiritual leader.

In France

In 1932 Mucha left Prague for Nice, France at a time when Hitler’s speeches were taken more and more seriously while Czechoslovakia was celebrating 15 years of independence. Gone was the optimistic air that permeated Mucha’s Sarah Bernhardt portrayals. In “Woman with a Burning Candle,” painted in 1933, a brooding woman wearing flowing robes and the coat-of-arms of the Czechoslovak Republic stares at a candle that has been burning down for a lengthy period of time. Wax oozes onto a wooden stand. The woman protects the nation’s flame as she ponders over the uncertain future of her country during its 15th anniversary year.

Back in Czechoslovakia, health problems and death

After his sojourn in France, Mucha returned to a very different Czechoslovakia than the one he had left. As Nazism spread, Mucha’s works and his Slav nationalism were belittled and considered to be reactionary. In 1936 his health worsened. His anxiety about the future of Czechoslovakia added to the physical deterioration. When the Nazis stormed into Prague and set up the Protectorate of Bohemia and Moravia in March of 1939, the 79-year-old Mucha, a well-known Freemason, Judophile, and symbol of democratic Czechoslovakia, was at the top of the Gestapo’s list. The once-respected artist came down with pneumonia during grueling interrogations and died July 14, 1939, from a lung infection. He is now buried in Prague’s Vyšehrad cemetery among other elite Czechs.

The fate of the Slav Epic

The fate of the Slav Epic has not been rosy. The canvases were stored underground during the Nazi Occupation. When the Communists took control, Mucha’s work was frowned upon as petty-bourgeois. The rolled-up canvases were transferred to the obscure Moravský Krumlov chateau in south Moravia but did not go on display there until 1963. During the late 1960s, however, there was a huge revival of Mucha and Mucha-like images in advertisements and posters. In 2010, when the City of Prague requested Moravský Krumlov to give back the Slav Epic, over 1,000 people voiced their objections in a demonstration. The following year the City of Prague forcefully removed the canvases and transported them to Prague. A fierce argument over where the paintings should be housed ensued. Since May 15, 2012, they have been exhibited at Prague’s Trade Fair (Veletržní ) Palace, where visitors first viewed the canvases in 1928.

The Mucha Foundation and the Mucha Museum

Thanks to the Mucha Foundation, operated by Alphonse’s grandson John, viewers all over the world have been able to enjoy Mucha’s captivating designs. During the 1990s, exhibitions took place in the Czech Republic, Japan, Germany, the USA, and other places while in this century the canvases have traveled throughout the Czech Republic as well as to Taiwan, Germany, Finland, Spain, Austria, and Hungary, for instance. The Mucha Museum in Prague opened its doors in 1998.

Mucha’s legacy

The ability to apply Mucha’s work to everyday objects certainly adds to his popularity. His versatile and provocative style is also rich with hidden symbolism that is never superficial. Mucha’s creations are by no means mere ornamentation but rather convey mystical and idealist values in a symbolic and dynamic way.

The ability to apply Mucha’s work to everyday objects certainly adds to his popularity. His versatile and provocative style is also rich with hidden symbolism that is never superficial. Mucha’s creations are by no means mere ornamentation but rather convey mystical and idealist values in a symbolic and dynamic way.