Bohumil Hrabal – the Sad King of Czech Literature

By Tracy A. Burns

February 3, 1997: The Death of the Sad King of Czech Literature, Bohumil Hrabal

Suicide or accident?

When Bohumil Hrabal either jumped or fell from a fifth floor window of Prague’s Bulovka Hospital while feeding pigeons at 2:30 p. m. on February 3, 1997, it marked the end of a phenomenal literary career spanning six decades and contributing enormously to Czech culture. His death from the fifth floor has an undoubted symbolic dimension, whether sought or merely coincidental: In his works he wrote about philosophers and writers who had jumped to their deaths from the fifth storey and even confessed that he sometimes wanted to jump from the fifth floor window of his flat. Whether he did jump or whether he fell will forever remain a mystery. Yet one thing was for certain. The sad king of Czech literature was dead.

When Bohumil Hrabal either jumped or fell from a fifth floor window of Prague’s Bulovka Hospital while feeding pigeons at 2:30 p. m. on February 3, 1997, it marked the end of a phenomenal literary career spanning six decades and contributing enormously to Czech culture. His death from the fifth floor has an undoubted symbolic dimension, whether sought or merely coincidental: In his works he wrote about philosophers and writers who had jumped to their deaths from the fifth storey and even confessed that he sometimes wanted to jump from the fifth floor window of his flat. Whether he did jump or whether he fell will forever remain a mystery. Yet one thing was for certain. The sad king of Czech literature was dead.

Characteristics of Hrabal´s Writing

Hrabal was noted for his grotesque, absurd and irreverent humor and anecdotes, not hesitating to “descend” sporadically into the Prague dialect. While he is most remembered for his fiction, he scribed captivating poetry early in his career. Perhaps he is best known for creating the pábitel, sometimes translated into English as palaverer – a dreamer living on the outskirts of society. By experiencing tragedy, the pábitel learns how to be content with life and how to find beauty in even the most horrible conditions. The pábitel is also much given to putting his thoughts into words, which frequently produces meandering whimsical anecdotes to make the reader laugh or cry. It is this propensity that probably suggested to his translator that the pre-existing English “palaverer” could be extended to embrace what it meant to be a Hrabalesque pábitel, a word that had scarcely any antecedents.

The early years of Bohumil Hrabal

Bohumil Hrabal, baptised as Bohumil František Kilián, was born in the Židence district of Brno in Moravia on March 28, 1914 to unwed mother and actress Marie Božena Kiliánová. Living with his grandparents until he was three, Hrabal enjoyed watching the funeral processions that passed by his house four times a week, and this ritual greatly influenced his penchant for the grotesque. In 1916 his mother married František Hrabal, an accountant for a brewery, and the three moved to the Bohemian-Moravian Highlands town of Polná. His brother Slávek was born in September of 1916 when he was three. Hrabal’s parents were active in amateur theatre, and at age four the future writer took up acting. In 1919 the family moved to Nymburk, where his father was employed as a brewery manager.

A significant event in Hrabal’s life took place in 1924, when he was 10: His Uncle Pepin moved in with the family. An outcast from society, Uncle Pepin loved telling absurd tales and Hrabal would later incorporate both Uncle Pepin and his anecdotes into his fiction. In the classroom Hrabal was by no means the model student. He often misbehaved and had no interest in the Czech language or Czech literature. In fact, he flunked out of a high school in Brno and another in Nymburk.

University Years

Then things changed. Before he was admitted to the Law School of Charles University, Hrabal developed an interest in philosophy and art. He even taught himself Latin and played both the piano and trumpet. In 1934 he became a law student, solely choosing the subject to please his mother. He became enraptured by existentialism and French literature, specifically by the works of Arthur Rimbaud and François Rabelais. He also admired the irony, absurdity and black humor of Franz Kafka. Hrabal’s first published work came in 1937, at age 24, in Nymburk’s Občanské Listy, where his piece titled “It’s Raining” appeared.

Postponed graduation and odd jobs

This future stellar author had one year of university to go when the Nazis took over in 1939 and closed all Czech universities. Hrabal went back to Nymburk to do odd jobs. In 1942 he found himself working as a trainee lawyer, while in 1945 he was a train dispatcher in Kostomlaty, where he was almost killed by Nazi soldiers. After the war he returned to Prague, and he obtained his law degree in March of 1946. He joined the Communist Party but dropped out a year later. Then Hrabal had a myriad of jobs, working as an insurance broker and traveling salesman, to name but two. In 1948 he made his book-length debut as a poet with the lyrical A Lost Alley (Ztracená ulička). Encountering the lively Prague Surrealist scene in the 1940s would greatly influence his work later on.

The Poldi steelworks

In 1949 he went to work at the Poldi steelworks in Kladno, not far from Prague. During his first year in Kladno, the character of Uncle Pepin made his debut in the story “The Sufferings of Old Werther.” Hrabal experimented with “total realism,” a style that he adopted following his surrealist phase and which involved mirroring the everydayness of life in an original way. During the 1940s he also moved to Na hrázi 24 in the working class Libeň district of Prague, a place where he would live for almost 25 years, until 1973. In 1952 a crane fell on Hrabal, putting an abrupt end to his career in the steelworks.

The 1950s: from paper baler to stagehand and writer

Then Hrabal became a paper baler on Prague’s Spálená Street while writing his fiction on a German typewriter with no Czech diacritics. During 1956 the Society of Czech Bibliophiles (Spolek českých bibliofilů) printed 250 copies of his book, People’s Conversations (Hovory lidí). His novel Jarmilka (his first Total Realist text), set in the steelworks, did not pass the censors. In 1956 he married Eliška Plevová, a German-Czech kitchen worker in Prague’s Hotel Paris, and they bought a cottage in Kersko, home to his many cats. After obtaining a literary stipend from the Literary Fund in 1959, he divided his time between writing and working part-time as a stagehand at Prague’s S.K. Neumann Theatre. He wrote a collection of stories called Larks on a String (Skřivánci na niti), which became a film in 1969. It took four years for the book to pass the censors. His work during the 1950s often was set in the Poldi steelworks and dealt with finding the simple, hidden beauty there despite the harsh reality. Hrabal wrote both poetry and prose at this time and further developed the pábitel type. The stories he scribed from 1957 to 1959 were called Pearls of the Deep (Perlička na dne). They included collage and montage elements and emphasized natural dialogue.

The successful 1960s – until 1968

The 1960s proved a successful period for Bohumil Hrabal – that is, until 1968. Československý spisovatel published his Pearls on the Bottom during 1963, and the collection won an award. A year later it was made into a film. Other books that followed during the 1960s included The Palaverers (Pábitelé, 1964), Dancing Lessons for the Advanced in Age (Taneční hodiny pro starší a pokročilé, 1964), Closely Watched Trains (Ostře sledované vlaky, 1965), Advertisement for the House I Don’t Want to Live in Anymore (Inzerát na dům, ve kterém už nechci bydlet), World Cafeteria/ The Death of Mr. Baltisberger (Automat Svět, 1966), This Town is Jointly Administered by its Inhabitants (Toto město je ve společné péči obyvatel), of which he wrote only a couple of pages, the bulk being an artful jumble (montage sui generis) of photos and quotations from other sources, and Murder Ballads and Other Legends (Morytáty a legendy, 1968). The 1968 film Closely Watched Trains won a prominent award in Czechoslovakia and nabbed an Oscar in the USA. Hrabal also traveled abroad during the 1960s – to Paris, New York and Moscow. His writing during this decade was characterized by grotesque humor and absurdity while Dancing Lessons for the Advanced in Age featured one never-ending sentence written in a stream-of-consciousness and associative imagery format.

Hrabal´s writing in the 1960s

During the 1960s Hrabal employed bawdy, grotesque and absurd humor and incorporated the Dadaist collage format in his works. He battles absurd situations and hardships wielding the weapon of a loud, defiant laugh. The Death of Mr. Baltisberger, written from 1957 to 1964, incorporated black humor and anecdotal narratives and displayed a dream-like quality. Hrabal’s characters are colorful, even unforgettable. In the tale “The Palaverers,” Mr. Burgán accidently gets a sickle stuck in his head, which inspires his son Jirka to paint a picture. As usual, Hrabal uses colloquial, Prague dialect Czech. In Dancing Lessons for the Advanced in Age, the main character is a 70-year old man who had worked as a shoemaker and had served as a soldier during the days of the Habsburg Empire. He brags to a young woman about his exploits and talks to himself as well. In one description the protagonist describes a man who “once…sang with such passion that his fly split open.” Real characters also appear in the story, including Czech writer Egon Bondy and German author Johann Wolfgang von Goethe.

Closely watched trains

Perhaps Hrabal’s best known work is Closely Watched Trains from 1965. Set in a small Czechoslovak town during the last days of the Nazi Occupation, it features a young dispatcher who has recently attempted suicide because of sexual problems. Again the characters are vivid as black humor abounds. In protest at the German atrocities against Poland, dispatcher Hubička strangles his Nuremberg pigeons and raises Polish silverpoints instead. Also, Hubička prints station stamps on the behind of a female colleague and is reprimanded for demeaning the German language because the stamps consisted of German words. In this work Hrabal employs a humor of cynicism injected with sharp satire. Laughter, it appears, acts as a kind of resistance to an era that was not funny at all. To be sure, Hrabal’s humor is the humor of survival.

A banned author

After the Soviet tanks crushed the Prague Spring of liberal reforms in August of 1968, Hrabal found himself a banned author in his country. He was thrown out of the Writers’ Union, and his books could only appear in underground, illegal presses as samizdat texts. The 1970s were fraught with police interrogations and depression. Yet it was under these harsh and miserable conditions that Hrabal created some of his best works. He wrote I Served The King of England (Obsluhoval jsem anglického krále, 1971), with the now canonical English title actually a mistranslation for “I waited on…,” The Little Town Where Time Stood Still (Městečko, kde se zastavil čas, 1973), The Gentle Barbarian (Nežný Barbar, 1973), Cutting It Short (Postřižiny, 1974), Too Loud A Solitude (Příiš hlucná samota, 1976), Snowdrop Festival (Slavnosti sněženek, 1978) and Beautiful Sadness (Krasosmutnění, 1978). Hrabal finally gave in to the Communists’ pressure and signed the anti-Charter denouncing the Charter 77 document calling for human rights and freedom, drafted by dissidents. While he was an officially accepted author again, young dissidents protested by burning his books. Even then, Too Loud A Solitude could only be published in samizdat and abroad.

Hrabal´s writings in the 1970s and I served the king of England

During 1970 Hrabal’s Buds (Poupata) was burned by the Communists. He was, however, able to publish Home Work (Domácí úkoly z pilnosti, 1970) officially, though. His 1971 I Served The King of England centers on the protagonist Jan Dítě, who yearns to belong to the most powerful social stratum and thinks money is everything. The novel takes place from the end of the democratic First Republic through the Nazi Occupation to the initial years of Communist rule. The young main character works as a waiter in exclusive hotels and earns much money. Dítě considers making money the means by which to ensure that he will belong to the politically correct upper class society. He marries the Nazi supporter Liza and achieves his dream of becoming a millionaire by selling the stamps she stole from Polish Jews after she dies in an air raid. Yet no one recognizes him as a millionaire because he profited from the war.

In 1976 Hrabal wrote Too Loud A Solitude as a protest against the banning of books during the rigid normalization period of the 1970s. The protagonist, Haňta, has been a paper baler for 35 years and saves books that he is supposed to compact because the government deems them not worthy of existing. Saving books is his life. One scene that illustrates Hrabal’s bawdy, witty humor involves Haňta recalling his love affair with the Roma Manča. While they are at a dance, moments after Manča returns from the restroom “…her ribbons had dripped into the pyramid of feces rising up to meet the board she sat on, and when she ran out into the brightly lit room and started dancing, she splashed and splattered the dancers…” To his great dismay, Haňta discovers that at other more modern hydraulic presses, employees work more quickly and efficiently as the job loses all individuality. Finally, he commits suicide after being assigned to compact only clean paper.

The 1980s: In-house weddings and others

Hrabal’s most significant accomplishment in the 1980s proved to be the trilogy In-House Weddings (Svatby v domě), but he also wrote Harlequin’s Millions (Harlekýnovy milióny, 1981), Poetry Clubs (Kluby poezie, 1981) and Life Without a Tuxedo (Život bez smokingu, 1986). In 1987 his wife died of cancer. Still, he did gave the intriguing book length interview that would appear as Pirouettes on a Postage Stamp (Kličky na kapesníku), published unofficially by underground Pražská imaginace. During the end of the 1980s, he traveled to the USA and Moscow. In 1988 his former home on Na hrázi Street was demolished to make way for a Metro station.

Hrabal´s writings in the 1980s: The trilogy

The first volume of the trilogy, In-House Weddings (Svatby v domě, 1986), depicts the banality of everyday life and straddles the line between autobiography and fiction. The protagonist celebrates by holding weddings and creating spontaneous happenings in his Libeň flat. The second volume, Vita Nuova (1986), deals with Hrabal’s life from 1957 to 1959, when he got married and left his job as a paper baler to work in the theatre. The third volume, Vacant Lot (Proluky, 1986), tracks his life from 1963, when Hrabal’s first book is accepted for publication, to the turbulent 1970s, when he is banned as an author. It is significant that the first volume is narrated by his wife whose German background brands her as someone with a bourgeois history.

The 1990s: worldwide recognition and the pub

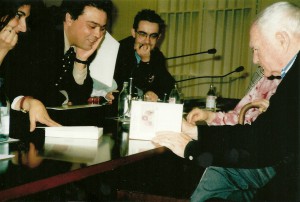

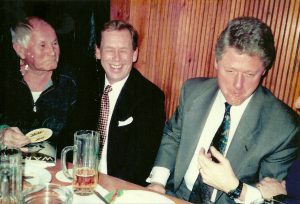

Hrabal spent most of his time in the 1990s drinking beer at the Golden Tiger (U zlatého tygra) pub in downtown Prague and traveling to Kersko to feed his many cats. In 1991 the first of 19 volumes of his collected works came into print. The last volume was published in 1997. His works from the democratic days include Total Fears: Letters to Dubenka (Totální strachy, 1990), November Hurricane (Listopadový uragán, 1990), Underground Rivers (Ponorné říčky, 1991), Pink Cavalier (Růžový kavalír, 1991) and Aurora on the Sandbank (Aurora na melčině, 1992). Collections of his stories and poetry also came into print. He won the Jaroslav Seifert prize for his In-House Weddings trilogy during 1993. Hrabal also gave lectures and readings abroad and accepted foreign literary awards and honorary degrees. In January of 1994, the acclaimed author met then U.S. President Bill Clinton and Ambassador to the United Nations Madeleine Albright at the Golden Tiger.

Hrabal spent most of his time in the 1990s drinking beer at the Golden Tiger (U zlatého tygra) pub in downtown Prague and traveling to Kersko to feed his many cats. In 1991 the first of 19 volumes of his collected works came into print. The last volume was published in 1997. His works from the democratic days include Total Fears: Letters to Dubenka (Totální strachy, 1990), November Hurricane (Listopadový uragán, 1990), Underground Rivers (Ponorné říčky, 1991), Pink Cavalier (Růžový kavalír, 1991) and Aurora on the Sandbank (Aurora na melčině, 1992). Collections of his stories and poetry also came into print. He won the Jaroslav Seifert prize for his In-House Weddings trilogy during 1993. Hrabal also gave lectures and readings abroad and accepted foreign literary awards and honorary degrees. In January of 1994, the acclaimed author met then U.S. President Bill Clinton and Ambassador to the United Nations Madeleine Albright at the Golden Tiger.

Hrabal´s writings from 1989-1997

In many of Hrabal’s works from this era, the author is the narrator, communicating via letters, for example, and becoming introspective and nostalgic. The journalist feuilletons in Total Fears consist of love letters to a Stanford University student. The nostalgic reflections include reportage of the 1989 Revolution. In The Magic Flute (Kouzelná flétna, 1990) Hrabal describes the atmosphere in Prague during January of 1989, when citizens protested against the regime by laying flowers at the statue of Saint Wenceslas in honor of the 20th anniversary of Jan Palach’s self-immolation. Anecdotes plus grotesque, dry and rough humor characterize this work. In Cassius’ Evening Fairytales (Večerníčky pro Cassia, 1993), the author/narrator talks to one of his feline friends and makes Cassius into a conquering classical Greek hero who has triumphantly come home to a glorious new beginning as he returns to a new country. The humor is grotesque and anecdotal, written in Prague dialect and emphasizing the historical oral tradition of the tale.

The end of the sad king of Czech literature

At the end of 1996, Hrabal was hospitalized with neuralgia. He was about to be released when he jumped or fell on February 3, 1997. This legendary Czech author is buried in a coffin with the inscription of the Polná Brewery, the place where his mother and stepfather met, in the family crypt at Hradišťko. With his writings translated into 27 languages, Bohumil Hrabal is slowly but surely becoming a household name in the literary world.

NOTE: The quotations from Dancing Lessons for the Advanced in Age and Too Loud A Solitude are taken from the English translations by Michael Henry Heim.