Franz Kafka, Prague Jewish Author

By Tracy A. Burns

Childhood

Franz Kafka grew up in Prague, in the labyrinthine Old Town and Jewish Town, their narrow streets, passages, and courtyards that seem to jump out of his novel The Trial caught between reality and fiction in the Bohemian capital that he called home, a place where Czechs, Germans, and Jews intermingled. Born in Prague on July 3, 1883, in an apartment next to St. Nicholas’ Church near Old Town Square, Kafka was raised in a middle-class, Ashkenazi Jewish family during the Austro-Hungarian Empire, where German was the official language. The eldest of six children, Kafka had two brothers who died as infants, and his three sisters would be sent to concentration camps during the Nazi Occupation. Two of them expired in the Łódź camp, and another spent time in central Bohemia’s Terezín fortress before being shipped to Auschwitz. His father, Hermann Kafka, was ill-tempered and domineering, often lashing out at his eldest child. Hermann sold men’s and women’s fancy goods in a shop that was for a while located on the ground floor of Kinský Palace on Old Town Square, and his mother, the daughter of a successful brewer, spent her days helping him. The children had to be raised by governesses and servants.

Franz Kafka grew up in Prague, in the labyrinthine Old Town and Jewish Town, their narrow streets, passages, and courtyards that seem to jump out of his novel The Trial caught between reality and fiction in the Bohemian capital that he called home, a place where Czechs, Germans, and Jews intermingled. Born in Prague on July 3, 1883, in an apartment next to St. Nicholas’ Church near Old Town Square, Kafka was raised in a middle-class, Ashkenazi Jewish family during the Austro-Hungarian Empire, where German was the official language. The eldest of six children, Kafka had two brothers who died as infants, and his three sisters would be sent to concentration camps during the Nazi Occupation. Two of them expired in the Łódź camp, and another spent time in central Bohemia’s Terezín fortress before being shipped to Auschwitz. His father, Hermann Kafka, was ill-tempered and domineering, often lashing out at his eldest child. Hermann sold men’s and women’s fancy goods in a shop that was for a while located on the ground floor of Kinský Palace on Old Town Square, and his mother, the daughter of a successful brewer, spent her days helping him. The children had to be raised by governesses and servants.

Kafka’s education

His education in Judaism was limited to having a Bar Mitzvah and visiting the synagogue four times a year with his father, outings that Kafka despised. Kafka’s father sent his son to German schools in order to give him a better chance to be successful, though Kafka was also fluent in Czech. He attended elementary school in the Jewish Town’s Masná Street. At a strict, demanding high school in Kinský Palace, he earned good grades and studied subjects such as Latin, Greek, and history. Then the future author took classes at Charles Ferdinand University, today’s Charles University, first focusing on chemistry, but switching two weeks later to law. At the end of his first year there, he met a fellow student who would become his close friend and biographer, Max Brod, and also associated with classmate Felix Weltsch, who became a prominent journalist. Kafka also attended classes in German studies and art history and joined a club that organized literary events. He received his law degree in June of 1906.

Work history

In the fall of 1907, Kafka joined the Italian insurance company, Assicurazioni General, where he toiled for almost a year at Wenceslas Square 19, dissatisfied with his hours of 8 pm to 6 am because he could not focus well on his writing. He left the company in 1908 and began working at the New Town’s Na poříčí 7 with the Workers ‘ Accident Insurance Institute for the Kingdom of Bohemia, for whom he investigated cases of injury to industrial workers, decided on adequate compensation, and was responsible for the annual report. Successful although he hated his duties, Kafka was promoted several times and was known to be a top-notch worker. In 1911 he also helped his sister’s husband supervise an asbestos factory and found himself without much time for his writing endeavors.

Literary life

His literary life involved meeting with Brod and Weltsch in what they termed the Prague Circle, which was part of a larger Prague Circle composed of German-Jewish writers. Soon he was intrigued with Yiddish theatre and literature as well, sparking his interest in Judaism. He had become a socialist in 1898 and had gone to meetings of the Czech anarchist organization Klub mladých, which was anti-militaristic and anti-clerical.

Literary works

Kafka wrote in German, although his letters to Jesenká were in Czech. He saw only a few of his stories in print during his lifetime, and of all his novels, he only finished The Metamorphosis. Brod published Kafka’s creations from 1925 to 1935. His notebooks were a challenge to publish because it was not possible to organize them in chronological order as Kafka sometimes began writing in the middle or at the end. Diamant kept many of his notebooks and 35 of his letters, but they were taken by the Gestapo in 1933. Currently, there is an international search for these papers. In 2010 thousands of his writings, letters and sketches were discovered in four safety deposit boxes in a Zurich bank, sparking a legal feud over the ownership of the papers. Both the state of Israel, where Brod moved in 1939, and the Hoffe sisters, whose mother was Brod’s secretary, claim to own the manuscripts.

Kafka wrote in German, although his letters to Jesenká were in Czech. He saw only a few of his stories in print during his lifetime, and of all his novels, he only finished The Metamorphosis. Brod published Kafka’s creations from 1925 to 1935. His notebooks were a challenge to publish because it was not possible to organize them in chronological order as Kafka sometimes began writing in the middle or at the end. Diamant kept many of his notebooks and 35 of his letters, but they were taken by the Gestapo in 1933. Currently, there is an international search for these papers. In 2010 thousands of his writings, letters and sketches were discovered in four safety deposit boxes in a Zurich bank, sparking a legal feud over the ownership of the papers. Both the state of Israel, where Brod moved in 1939, and the Hoffe sisters, whose mother was Brod’s secretary, claim to own the manuscripts.

Personality

Kafka was convinced people thought he was ugly and repulsive, though he was really quite good-looking. He suffered from depression, social anxiety, migraines, and insomnia, among other illnesses. Some sources claim he was homosexual and had a schizoid personality disorder as well as anorexia.

Relationships

Felice Bauer, who resided in Berlin and worked with a Dictaphone company, became the woman in his life in 1912. They often wrote letters to each other and on two occasions were even engaged. But the relationship went sour in 1917, the year Kafka got tuberculosis and had to retire, financially supported by his family. In the early 1920s, another woman came onto the scene – Czech journalist and writer Milena Jesenská. In 1923 he lived in Berlin for a short period, residing with the 25-year-old Dora Diamant, a kindergarten teacher, an orthodox Jew. Focusing on his writing, Kafka also took an interest in the Talmud, which focuses on Jewish law, ethics, philosophy, customs, and history.

Return to Prague and death

He came back to Prague when his tuberculosis got worse and was checked into a sanatorium near Vienna, where he died on June 3rd, 1924 at the age of 40. He had asked his literary executor Brod to destroy all his published and unpublished works when he passed away, but, thankfully, Brod did not abide by his wish. He was interred in the New Jewish Cemetery of Prague’s Žižkov district on June 11, 1924, buried next to his parents under a two-meter obelisk at sector 21, row 14, plot 33.

Themes in his writings

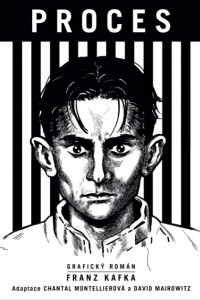

While Kafka’s works are open to numerous interpretations, his characters cannot communicate with others and find themselves consumed by anguish in absurd situations they cannot control. Protagonists who are victims hopelessly search for their own identity, a sense of security, and purpose. In The Trial Joseph K., after being arrested, searches for a court and the acquittal of a charge that has not been described to him. Kafka’s works utilize the grotesque and convey a profound sense of alienation. A sense of displacement and estrangement occurs even in familiar settings, and streets become menacing and unrecognizable. He satires bureaucracy in such works as The Castle, The Trial, and In the Penal Colony.

While Kafka’s works are open to numerous interpretations, his characters cannot communicate with others and find themselves consumed by anguish in absurd situations they cannot control. Protagonists who are victims hopelessly search for their own identity, a sense of security, and purpose. In The Trial Joseph K., after being arrested, searches for a court and the acquittal of a charge that has not been described to him. Kafka’s works utilize the grotesque and convey a profound sense of alienation. A sense of displacement and estrangement occurs even in familiar settings, and streets become menacing and unrecognizable. He satires bureaucracy in such works as The Castle, The Trial, and In the Penal Colony.

Guilt and despair are common themes. In The Metamorphosis the protagonist changes into a gross insect, and partially through his own guilty despair, dies a slow death. His troubling relationship with his father can be seen in his writings, too. In Amerika, the protagonist’s family ships him to America, where he tries to find a substitute father. Violence punctuates In the Penal Colony as the main character mutilates himself with his own torture instrument. In The Judgment, a father implores his son to commit suicide, and the son abides by his parent’s wish.

There is also a prominent transformation-deformation theme as some of his images are reminiscent of German expressionism. Misogyny and difficulty portraying women in a positive light can be found in his works, too. His female characters are usually grotesque, distant, bothersome, and impossible to love. The self as the center of the universe is another theme that figures in Kafka’s writings. Behind every character, there is Kafka and Kafka alone.

Kafka’s sights in Prague

There is a museum devoted to Kafka in Prague and a plaque on the building where Kafka was born next to St. Nicholas‘ Church. Not far from there, next to Old Town Hall on Old Town Square, the Minute House (once a tobacconist’s shop) used to be Kafka’s home. Both his father’s shop and Kafka’s high school were located in Old Town Square’s Kinský Palace. The Italian insurance company where he worked was situated at Wenceslas Square 19, and the Workers’ Accident Insurance for the Kingdom of Bohemia had its offices at Na poříčí 7. The house where Kafka lived at Golden Lane 22 on the Prague Castle grounds can be viewed by visitors. He even lived for a few months in the building that now houses the U.S. Embassy. Near the Spanish Synagogue in the Jewish Town, there is an intriguing monument honoring Kafka. Designed by artist Jaroslav Rona in 2003, the writer’s statue sits on the shoulders of a headless person who shows him which way to go. Kafka is buried next to his parents under a two-meter obelisk at sector 21, row 14, plot 33 in the New Jewish Cemetery.

There is a museum devoted to Kafka in Prague and a plaque on the building where Kafka was born next to St. Nicholas‘ Church. Not far from there, next to Old Town Hall on Old Town Square, the Minute House (once a tobacconist’s shop) used to be Kafka’s home. Both his father’s shop and Kafka’s high school were located in Old Town Square’s Kinský Palace. The Italian insurance company where he worked was situated at Wenceslas Square 19, and the Workers’ Accident Insurance for the Kingdom of Bohemia had its offices at Na poříčí 7. The house where Kafka lived at Golden Lane 22 on the Prague Castle grounds can be viewed by visitors. He even lived for a few months in the building that now houses the U.S. Embassy. Near the Spanish Synagogue in the Jewish Town, there is an intriguing monument honoring Kafka. Designed by artist Jaroslav Rona in 2003, the writer’s statue sits on the shoulders of a headless person who shows him which way to go. Kafka is buried next to his parents under a two-meter obelisk at sector 21, row 14, plot 33 in the New Jewish Cemetery.