Jaroslav Hašek and his novel “The Good Soldier Svejk”

By Tracy A. Burns

April 30, 1883, and the early years of Jaroslav Hašek

On April 30, 1883, in Prague’s Školská Street of the respectable New Town, Jaroslav Hašek, the future writer, hoaxer, and anarchist, was born. At that time, in the Bohemian province of the Austro-Hungarian Empire, Czechs were oppressed by the Austrians, and German was the official language. Hašek would come to understand the Czech-Austrian conflicts quite well. One of three children, the fun-loving vagabond came from a poor family, though his grandfather, František Hašek, had a claim to fame – he had participated in the Prague Uprising of 1848, when Czechs protested for more freedom within the monarchy and then became a member of the Austrian Parliament in Kroměříž, Moravia. Jaroslav’s father was an alcoholic who taught math and physics at an Austrian high school and later became an actuary in a bank. He died from alcohol abuse when his to-be famous son was only 13 years old. During the first 10 years of his life, Hašek moved seven times. The lazy and badly behaved Jaroslav also joined a gang. Although he got excellent grades during his first two years at the Imperial and Royal Junior Gymnasium, Hašek was later expelled for his escapades.

On April 30, 1883, in Prague’s Školská Street of the respectable New Town, Jaroslav Hašek, the future writer, hoaxer, and anarchist, was born. At that time, in the Bohemian province of the Austro-Hungarian Empire, Czechs were oppressed by the Austrians, and German was the official language. Hašek would come to understand the Czech-Austrian conflicts quite well. One of three children, the fun-loving vagabond came from a poor family, though his grandfather, František Hašek, had a claim to fame – he had participated in the Prague Uprising of 1848, when Czechs protested for more freedom within the monarchy and then became a member of the Austrian Parliament in Kroměříž, Moravia. Jaroslav’s father was an alcoholic who taught math and physics at an Austrian high school and later became an actuary in a bank. He died from alcohol abuse when his to-be famous son was only 13 years old. During the first 10 years of his life, Hašek moved seven times. The lazy and badly behaved Jaroslav also joined a gang. Although he got excellent grades during his first two years at the Imperial and Royal Junior Gymnasium, Hašek was later expelled for his escapades.

Odd jobs, business school, and writing

After leaving school at age 15, Hašek mixed drugs for a pharmacist and then took classes in business at the Commercial Academy, where poet S.K. Neumann and prose writer Jan Otčenášek had attended and where legendary scribe Alois Jirásek taught. In 1902, he graduated with honors, though he made fun of the administration in his published writings. From 1901 to 1904, he had seen his name in print on 40 stories. He was also enamored with anarchist Russian authors. After his business studies, Hašek became a bank clerk but quit when he chose to go to a pub instead of running an errand. Later he sold dogs for a living.

Anarchist inclinations and writing success

Hašek became editor of an anarchist journal in 1907. His behavior was unruly, to say the least. He often found himself arrested or in prison for charges such as vandalism or assaulting a police officer. Smitten by Jarmila Mayerová in 1907, he was dismayed when her parents forbade her to marry him, claiming that his lifestyle was too wild and erratic. In 1910, though, he did marry Jarmila. Unfortunately, their marriage was not happy and ended in three years. Still, the couple did not get a divorce. While his love life was not faring well, his career as a writer and journalist blossomed. By 1909, he had already published 64 stories; in total, about 1,500 of his stories would be printed. For a short time, he was editor of a magazine called Animal World, but he was fired when the management found out he was describing nonexistent animals.

World War I and Russia

The pubgoer fought in the world war, but in 1915 he was captured in Russia and sent to a prisoner-of-war camp where he served as a commander’s secretary. His stint doing office work was short-lived, however. In 1916 he joined the Czech Legion. The Russian Revolution of 1917 did not hinder Hašek from staying in Russia, where he then joined the Bolsheviks and the army. There, he became a bigamist when he wed for the second time, while still married to Jarmila. When he was residing in Russia, it was reported in Czech newspapers that he had died.

Back in Prague and Lipnice to his death

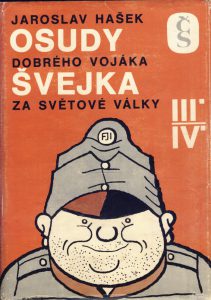

After moving back to Prague in 1920, he poked fun at his own obituary, penning an article called, „How I Met the Author of My Obituary.“ Most importantly, the jester created the four-volume epic The Fortunes of the Good Soldier Švejk in the First World War from 1920 to 1923, though the Švejk character had already appeared in another work. Suffering from tuberculosis caught during the war, he died in the village of Lipnice, where he had resided for a year and a half, on January 3, 1923, at the tender age of 39. Czechs did not pay much attention to his obituary because the Czechoslovak Finance Minister, Alois Rašín, had been assassinated by an anarchist. While the headstone on Hašek’s grave in Lipnice was very plain, later it would take on a more lavish appearance with an open book of granite and a gilt inscription that read, „Austria, never were thou so ripe to fall, never were thou so damned.“

Hašek’s stories

While Hašek is best known for his creation of the lovable idiot Josef Švejk, he also excelled at story writing, where he employed black humor and the grotesque. In his story „The Emperor Franz Joseph’s Portrait,“ the stationer Petiška tries to sell postcards of Emperor Franz Joseph at a discount when the war breaks out because he mistakenly believes Czechs will be patriotic to the Austrian cause. Czechs have no interest in the postcards and no enthusiasm for the war. When Petiška puts the postcards in the back of his store, his cat goes to the bathroom on them. In Hašek’s creation, “The Demon Barber of Prague,” a barber, Mr. Špachta, makes anti-Arab and anti-Turk comments as he butchers his customer, a judge. His violent words breed violent action. Finally, the barber decapitates the customer.

The Good Soldier Švejk

In the picaresque novel about soldier Švejk during the first world war, the protagonist has been branded an idiot by the official Austrian authorities even though, ironically, he professes loyalty to the Habsburg Empire. The lovable soldier messes up orders by taking them literally. The mammoth novel concerns the plight of the common man in the dawn of a new age, and it also covers themes of anti-clericalism and anti-militarism. The comic protagonist is a trader of dogs with forged pedigrees, too. The masterpiece is noted for its anecdotes, colloquial, Prague-dialect Czech, satire, grotesqueness, parody, irony, sarcasm, collage, and fragmentation as well as the juxtaposition of the historical and the trivial. Hašek wields the weapon of black humor in order to portray tragedy, specifically the death and destruction wrought by the first world war. Humor accents the absurdity of the events. The work is a collage of many styles – journalistic prose, monologues that make up anecdotal tales, slapstick comedy, stanzas from national and military songs, personal letters, official announcements, and parodied newspaper articles as well as vulgar phrases in various languages.

In the picaresque novel about soldier Švejk during the first world war, the protagonist has been branded an idiot by the official Austrian authorities even though, ironically, he professes loyalty to the Habsburg Empire. The lovable soldier messes up orders by taking them literally. The mammoth novel concerns the plight of the common man in the dawn of a new age, and it also covers themes of anti-clericalism and anti-militarism. The comic protagonist is a trader of dogs with forged pedigrees, too. The masterpiece is noted for its anecdotes, colloquial, Prague-dialect Czech, satire, grotesqueness, parody, irony, sarcasm, collage, and fragmentation as well as the juxtaposition of the historical and the trivial. Hašek wields the weapon of black humor in order to portray tragedy, specifically the death and destruction wrought by the first world war. Humor accents the absurdity of the events. The work is a collage of many styles – journalistic prose, monologues that make up anecdotal tales, slapstick comedy, stanzas from national and military songs, personal letters, official announcements, and parodied newspaper articles as well as vulgar phrases in various languages.

Responding to the decay of the Monarchy

Traditionally allies with Serbia, Russia, and France, Czechs were forced during the first world war to fight for Austro-Hungary. A victory for the Habsburgs and Central Powers would have crushed Czech dreams for autonomy and would have meant even more years of German oppression. By writing this book, Hašek is responding to the Habsburg Empire’s domination of Bohemia and Moravia as he illuminates the decay of the monarchy which had controlled the Czech lands since 1526. The practical joker depicts the Austro-Hungarian Empire as crumbling internally in its judicial and legal systems, its police force, and its bureaucracy. The author takes shots at the royal family, the police, the Church, the legal system, bureaucracy, prisons, doctors, military hospitals, and lunatic asylums, to name a few.

Poignant moments in Švejk

Many scenes in the Švejk novel are poignant and memorable. For example, the pub owner Palivec placed a portrait of Emperor Franz Joseph in a back room because flies relieved themselves on it so often. Palivec was arrested for high treason after telling plainclothes officer Bretschneider why the picture no longer hung on the wall. Švejk’s reaction to his landlady, Mrs. Muller, after she informs him about the assassination, is telling. He asks Mrs. Muller which Ferdinand was killed – he knows one who is a messenger at a chemist’s and had drunk a bottle of hair solution. The other Ferdinand he knows collects dog manure. Švejk‘s exclamation of „Long live the Emperor!“ ironically convinces army experts that he should be placed in a mental institution. Švejk is an anti-hero who never fires a gun. Instead, he is playing cards, drinking cognac, singing to himself, and marching in the wrong direction.

Švejk as a symbol of Czech humor and humanity

The book is known for its specifically Czech humor because the protagonist responds to conflict passively, laughing at circumstances that might make others cry. By not taking action, Švejk influences the outcome of events. Other Czech traits include the singing of national songs and the Prague-dialect language which was frowned upon by the Austrian authorities. Yet the endearing Švejk is not only a symbol of Czechness; he is a symbol of humanity.

The bad bohemian and worldwide recognition

Despite the book’s worldwide success, Hašek had not always been revered in the Czech lands. From his death until the German Occupation in 1939, he was branded an unruly bohemian. During the Nazi era, his books were burned. From 1945 to 1948, during the second democratic Czechoslovak Republic, Hašek’s writings earned only a limited sense of acceptance. From the Communist coup of 1948 to the present, his works rank among the best in Czech literature. The Good Soldier Švejk has been translated into more than 60 languages.