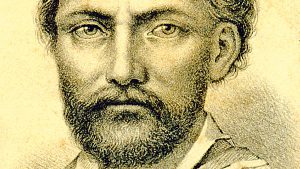

Karel Hynek Mácha: A leading poet of Czech Romanticism

By Tracy A. Burns

This pioneer of Czech Romanticism died on November 6, 1836, at the tender age of 25. However, in such a short time he managed to found modern Czech poetry and authored works of prose as well. His best-known verse, one of the best poems in Czech literature, is May (Máj), a lyric epic poem about a prisoner about to be executed. Yet his writings did not receive much praise during his lifetime, and May was his only book to be published when he was alive.

This pioneer of Czech Romanticism died on November 6, 1836, at the tender age of 25. However, in such a short time he managed to found modern Czech poetry and authored works of prose as well. His best-known verse, one of the best poems in Czech literature, is May (Máj), a lyric epic poem about a prisoner about to be executed. Yet his writings did not receive much praise during his lifetime, and May was his only book to be published when he was alive.

Childhood

Born as Ignác Mácha on November 16, 1810, he first opened his eyes in the building At the White Eagle on Prague’s Újezd Street in today’s Smíchov district. His father Antonín worked as a foreman of a mill and later owned a shop while his mother, Marie Anna Kirchnerová, came from a very musically talented family. He had one brother, Michal, who was two years younger. Suffering from financial woes, the Mácha family had to move several times to poverty-ridden neighborhoods. Finally, when Mácha was 16, they settled in the building across from the Church of Saint Ignác on today’s Charles Square in the New Town. Mácha was educated at schools headed by Piarists. At his high school on Na Příkopě street in Prague’s first district, he excelled at math and drawing and became fluent in German. He also was a stellar student of Czech and Latin.

University days

Mácha went on to study at Prague University’s Philosophy Faculty. It was here that he attended lectures by Josef Jungmann, a writer, and translator who put together the first Czech encyclopedia. Jungmann inspired Mácha to write in Czech after the young poet had written his initial literary endeavors in German. His first poem to be published in Czech, “Saint Ivan,” came out in 1831. Mácha read works by foreign authors, such as Lord Byron, a British poet who played a major role in the Romantic movement. He also read the works of Adam Mickiewicz, a Polish poet of the Polish Romantic period. Mácha also supported the Poles in their uprising against Russia in the Crimean War. The aspiring author focused on law from 1832 to 1836. No one knows exactly what Mácha looked like, but it is thought that he was tall and energetic with a long face and dark blue eyes.

His writings

Mácha scribed historical novels as well as poetry. The Hangman was four volumes long. Křivoklád, today spelled as Křivoklát, dealt with the life and times of Czech king Václav IV, who reigned from 1378 to 1419. His most extensive work was the novel Gypsies, penned from 1835 to 1836. His autobiographical sketches can be found in Pictures From My Life. Other prose included The Krkonoše Pilgrimage, The Return, Sázava Monastery, and The Dream. His Secret Diary from the fall of 1835 described in ciphers his sexual exploits and relationship with his girlfriend Eleonora (Lori) Šomková. Mácha kept a literary diary as well. His travelogue, Diary of Travel to Italy, describing his journey to Venice, was written in 1834.

The poem May (Máj)

While Mácha’s work May is highly revered today, it was rejected by publishers during his lifetime. Undeterred, he published it himself, printing 600 copies in April of 1836. The tragic plot revolves around the thief Vilém, who is in prison awaiting execution. He killed his father, who had banished Vilém from his home when he was a child. Pondering over his fate, Vilém questions the meaning of life. The day of execution is in mid-May, when nature is blossoming, so alive, as Vilém faces death. Written mostly in iambic pentameter, the poem includes four songs and two intermezzos. Metaphors, oxymorons, and cacophony abound as Mácha explores metaphorical ideas. The poem celebrates love, country, and the beauty of spring. Existentialism, alienation, isolation, and surrealism feature in the text, too.

While Mácha’s work May is highly revered today, it was rejected by publishers during his lifetime. Undeterred, he published it himself, printing 600 copies in April of 1836. The tragic plot revolves around the thief Vilém, who is in prison awaiting execution. He killed his father, who had banished Vilém from his home when he was a child. Pondering over his fate, Vilém questions the meaning of life. The day of execution is in mid-May, when nature is blossoming, so alive, as Vilém faces death. Written mostly in iambic pentameter, the poem includes four songs and two intermezzos. Metaphors, oxymorons, and cacophony abound as Mácha explores metaphorical ideas. The poem celebrates love, country, and the beauty of spring. Existentialism, alienation, isolation, and surrealism feature in the text, too.

Harsh criticism

While May has been published more than 200 times and is considered one of the best Czech poems ever written, it received scathing criticism when Mácha published it. Critics called Mácha a nihilist and considered the work to be too individualistic. It was not until the 1850s that writers such as Jan Neruda and Kateřina Světla recognized the brilliance of Mácha’s verse. There was even a cult of Mácha fanatics, similar to the cult that followed Saint Wenceslas (Václav).

Life in the theatre

Mácha was a passionate theatergoer and amateur actor as well. During the 1834-85 season, he performed in 16 productions at the Kajetán Theatre. He dabbled in playwriting, but his plays remained unfinished. It was after a rehearsal during the winter of 1833-84 that he met the love of his life, Lori, with whom he had an illegitimate son. They planned to marry on November 8, 1836, but fate would intervene.

A penchant for traveling

An avid traveler, Mácha even went from Prague to northern Italy on foot, walking as many as 60 kilometers a day for six weeks. His demanding excursion took him through České Budějovice, Linz, Salzburg, and Innsbruck before he reached Venice and Trieste. He also stopped in Ljubljana and Vienna on his way back to Prague. Other travels took him from Prague to imposing Bezděz Castle via Mělník, Kokořín, Houska and Doksy. He made another trek to the Krkonoše Mountains with stops at Kost and Trotsky castles. Mácha even signed the visitors’ book at Sněžka Mountain on August 28, 1833. He loved to take trips to castles and ruins.

His death

After university Mácha went to work as a legal assistant in Litoměřice. He noticed a fire in the town on the night of October 23, 1836. Mácha helped put it out but became ill. Some sources say he drank sewage water. His health rapidly deteriorated in early November, and he died on November 6. The official cause of death was cholera, a form of cholera, but some sources claim he died of pneumonia or salmonella. Mácha was buried in a pauper’s grave in Litoměřice on November 8, the day he had planned to marry Lori. His brother Michal was one of the few in attendance. His remains stayed in that grave for 102 years. On November 17 the crowded Church of Saint Ignác in Prague held a requiem for him. His parents, Jungmann, students, and professors came to pay their respects.

His legacy

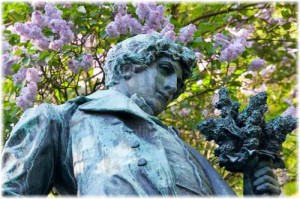

Mácha’s complete writings were published in 1861. In 1912 sculptor Josef Václav Myslbek’s statue of Mácha was placed on Prague’s Petřín Hill. Shortly after the 1938 signing of the Munich Agreement, which ceded the German-speaking Sudeten lands to The Third Reich, Czechs moved Mácha’s remains to Vyšehrad cemetery in Prague in what became a national demonstration against the Nazis. A lake was named after Mácha in 1961. Today, the month of May is celebrated as Mácha’s time of love and romanticism. The poem May has been set to music and made into films.

Mácha’s complete writings were published in 1861. In 1912 sculptor Josef Václav Myslbek’s statue of Mácha was placed on Prague’s Petřín Hill. Shortly after the 1938 signing of the Munich Agreement, which ceded the German-speaking Sudeten lands to The Third Reich, Czechs moved Mácha’s remains to Vyšehrad cemetery in Prague in what became a national demonstration against the Nazis. A lake was named after Mácha in 1961. Today, the month of May is celebrated as Mácha’s time of love and romanticism. The poem May has been set to music and made into films.