Life during the Communist era in Czechoslovakia

By Tracy A. Burns

The years of totalitarian rule in Czechoslovakia, from 1948 to 1989, were dark and dismal days, indeed. After the 1948 coup, Communist ideology permeated citizens’ lives and dominated all aspects of society. Czechoslovakia’s political decisions were dictated by the Soviet Union, and the country continued to rely on the Soviet Union even during the 1980s. Czechoslovakia was part of the Eastern Bloc and a member of the Warsaw Pact and Comecon.

Characteristics of life during Communism

Those who did not comply with socialism were not only interrogated, intimidated, and put under surveillance but also subject to house searches, during which the Secret Police invaded citizens’ privacy while searching for illegal literature. Bribes abounded; the presence of bugs in homes prevented people from speaking openly; there were long lines at the shops; people were imprisoned for filing complaints or signing petitions. Furthermore, the rich turned poor as owners of extravagant housing were given new accommodation in the country. Tradesmen were chosen to head companies. Members of the intelligentsia were forced to do menial jobs such as cleaning streets or washing windows. If a citizen defected, the family left behind was severely punished. People socializing with dissidents were interrogated and accused of subversion.

Those who did not comply with socialism were not only interrogated, intimidated, and put under surveillance but also subject to house searches, during which the Secret Police invaded citizens’ privacy while searching for illegal literature. Bribes abounded; the presence of bugs in homes prevented people from speaking openly; there were long lines at the shops; people were imprisoned for filing complaints or signing petitions. Furthermore, the rich turned poor as owners of extravagant housing were given new accommodation in the country. Tradesmen were chosen to head companies. Members of the intelligentsia were forced to do menial jobs such as cleaning streets or washing windows. If a citizen defected, the family left behind was severely punished. People socializing with dissidents were interrogated and accused of subversion.

The nightmarish 1950s

During the beginning of the brutal and nightmarish 1950s, Soviet Union Premier Joseph Stalin directed the Czechoslovak Communists to carry out purges, and the nation held the largest show trials in Eastern Europe. Over a six-year period, from 1949 to 1954, the victims included military leaders, Catholics, Jews, democratic politicians, those with wartime connections with the West as well as high-ranking Communists. Almost 180 people were executed. There was no such thing as a fair trial as judges cooperated with the country’s leadership. The defendants, branded guilty before the trial began, even had to rehearse their testimonies in advance, as if it all were some cruel play performed on a stage instead of in a courtroom. (During the 1960s, some of the victims were rehabilitated.)

The show trials of Rudolf Slánský and Milada Horáková

Two notable trials involved democratic politician and resistance leader Milada Horáková in 1950 and Communist politician Rudolf Slánský in 1952. Horáková, the only woman to be executed, was said to have organized a plot to overthrow the Communist regime. Her death sentence was condemned by personalities throughout the world, including Albert Einstein, Winston Churchill, and Eleanor Roosevelt. Instead of succumbing to international pressure, the Communists moved the date of her execution ahead of schedule. The trial was broadcast on public radio. Accused of high treason, the Communist Party claimed Slánský was a Titoist – someone who supported the socialist system formed by Yugoslavia’s leader Josip Broz Tito, in which a Communist country does not obey the Soviet Union but dictates its own socialist objectives. Slánský allegedly committed espionage. He was tried along with 13 others. Slánský and 10 of the accused were sentenced to death.

More purges

During the harsh normalization period of political repression after the crushing of the Prague Spring and its liberal reforms in August of 1968, more purges were carried out. In the purges from 1969 to 1971, however, no one was hanged. Instead, the accused were expelled from the Communist Party and lost their jobs. They were subject to interrogations and intimidation techniques and were followed by the secret police. High-ranking government personnel and leaders of social organizations were victims of these purges, and the reformists that had supported the Prague Spring were targets. Authors whose writings did not conform to socialism found their works banned, and other artists, such as actors and directors, were not permitted to take part in productions. Unlike the 1950s, the police saved violence for those who stubbornly opposed the intervention of Soviet troops in 1968.

Farmers: Enemies of the State

Farmers, especially wealthy ones referred to as “kulaks,” were enemies of the Communist regime. During the years of Stalinization, farms were nationalized in what was called collectivization. No one could own more than 50 hectares of land. While the lives of richer peasants were destroyed, poorer peasants were excited by the system. Communists blackmailed farmers and threatened them with imprisonment if they did not join cooperatives. Such farmers were publicly denounced and found themselves without supplies. Greedy farmers took positions on committees setting up the cooperatives and were rewarded by vacations abroad, the cooperative paying all expenses. Yet collectivization was inefficient and failed.

Religion: The greatest rival

Still, farmers were not the Communist Party’s greatest rival – religion was. People protested by setting up an underground movement of clergy and lay people from various denominations. The Communists took over Church property, closing down all 216 monasteries in the country during 1950 and most of the 339 convents. Some clergymen were murdered, while others found themselves sharing prison cells with murderers or the insane, or they were sent to labor camps or placed in the army. In 1950 the secret police planted weapons in a monastery and carried out a show trial accusing Catholic priests of spying. The ordained spent many years in prison.

The glorification of the worker

Under Communism workers were worshipped as heroes and exploited as propaganda for the regime. Miners, for example, received excellent pensions and comfortable housing. Workers had better salaries than university professors. The working-class employees who obeyed Communist doctrine were rewarded with holidays abroad – in Bulgaria, Romania, the Soviet Union, or Yugoslavia rather than in the West.

The system of education

Communist ideology permeated the politically-based education system. Students had to study subjects such as Marxism-Leninism. They learned by rote, not encouraged to discuss issues or form their own opinions. Applicants were accepted into university if they had working-class backgrounds, supported the Communist regime, and participated in Communist youth organizations.

The media

Also controlled by the government, the media was a mouthpiece for the Communist regime. Censorship became law in 1948. Television, for example, was imbued with official optimism as tractors and factories often appeared on the screen. Editorials were riddled with clichés, and platitudes abounded. During the normalization purges of 1969-70, dozens of magazines and journals were shut down.

Sporting organizations

The Communist era marked the end of the Sokol organization – Sokol means falcon – which had displayed a strong democratic tradition as far back as the 19th century. After 1948 the Spartakiáda festivals, held every five years, took place. In these sports shows thousands of gymnasts performed choreographed feats, emphasizing the importance of the group over the individual.

Czechoslovak culture

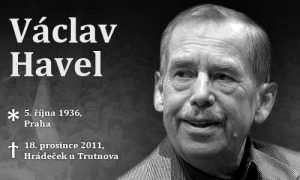

The Czechoslovak culture was allowed more freedom during the beginning of the 1960s. In 1958 Josef Škvorecký made his stellar debut as a novelist with The Cowards, a literary jewel about a young man interested in jazz and girls during the Nazi Occupation. Soon, though, the book would be banned by the Communist regime. New, liberal magazines came onto the literary scene. Czech comedy was an outlet for dissent and contained coded references against Communism. In the 1960s three of future Czechoslovak and Czech President Václav Havel’s absurdist plays were performed at Prague’s Theatre on the Balustrade, which opened in 1958. (Havel would later spend five and a half years in prison.)

The Czechoslovak culture was allowed more freedom during the beginning of the 1960s. In 1958 Josef Škvorecký made his stellar debut as a novelist with The Cowards, a literary jewel about a young man interested in jazz and girls during the Nazi Occupation. Soon, though, the book would be banned by the Communist regime. New, liberal magazines came onto the literary scene. Czech comedy was an outlet for dissent and contained coded references against Communism. In the 1960s three of future Czechoslovak and Czech President Václav Havel’s absurdist plays were performed at Prague’s Theatre on the Balustrade, which opened in 1958. (Havel would later spend five and a half years in prison.)

Masterful Czech films from this era include the Jiří Menzel-directed Closely Watched Trains, which is based on the novel by Bohumil Hrabal and intertwines comedy, tragedy, and irony. In June of 1968, writer Ludvík Vaculík published his infamous Two Thousand Words protest, describing the current political situation and encouraging citizens to take action. One personality that remained popular during the Prague Spring and Communist-era was singer Karel Gott, whose impressive career took off in the mid-1960s. The Communists frowned on the impact of Western music on socialist youth, and during the 1970s rock musicians and their fans were persecuted.

Illegal literature

During the 1970s and 1980s, many Czech and Slovak artists were put in prison or forced to emigrate. Dissidents were often harassed and sometimes imprisoned for speaking out against the regime. Those who signed the Charter 77 declaration of human rights were arrested, interrogated, and lost their jobs. Nonconforming literature was printed through underground channels as illegal samizdat texts produced on typewriters. By the mid-1980s, several underground publishing houses existed. Possession of samizdat material could lead to imprisonment. Despite the limitations of Czech literature, poet Jaroslav Seifert nabbed the Nobel Prize in 1984.

Adapting to the harsh reality

Yet during such harsh times, citizens were able to adapt to the deplorable conditions. They spent their weekends at their cottages, surrounded by nature, and most did not get involved in politics. Finally, the Velvet Revolution of 1989 brought an end to the nightmare that had lasted 40 years, and democracy once again resounded in Czechoslovakia.

Yet during such harsh times, citizens were able to adapt to the deplorable conditions. They spent their weekends at their cottages, surrounded by nature, and most did not get involved in politics. Finally, the Velvet Revolution of 1989 brought an end to the nightmare that had lasted 40 years, and democracy once again resounded in Czechoslovakia.

Museum of Communism in Prague

The museum focuses on the totalitarian regime from the February coup in 1948 to its rapid collapse in November 1989. The theme of the Museum is “Communism- the Dream, the Reality, and the Nightmare” and visitors will be treated to a fully immersive experience. Immersive factories, a historical schoolroom, an Interrogation Room, or the video clips in our Television Time Machine are all part of the experience. The museum is a great introduction before you step back even further in time and experience the wonders of The Golden City. Read our article about the Museum of Communism.