Life During the Nazi Occupation

By Tracy A. Burns

March 15, 1939: a horrific day in history

Adolf Hitler got his wish to conquer Czechoslovakia when German troops, fighting off a ravaging snowstorm and vehicles’ technical problems, marched into Prague on March 15, 1939, and took over Bohemia and Moravia. (Earlier, at the Munich Conference in September of 1938, Hitler had acquired the Sudetenland region of Czechoslovakia.) While German citizens of the capital city saluted and waved swastika flags, some Czechs let out heartwrenching sobs while others displayed anger as they were horrified, overcome with powerlessness and hopelessness. Czechs hurled snowballs at the vehicles and refused to give lost Germans directions. Numerous Czechs gathered in Wenceslas Square, where they sang the national anthem. A photo of first democratic president Tomáš Garrigue Masaryk was placed on the Tomb of the Unknown Soldier, later destroyed by the Nazis, on Old Town Square. That day Hitler made his first and last visit to Prague. The next morning he signed a declaration that officially created the Nazi Protectorate of Bohemia and Moravia.

Adolf Hitler got his wish to conquer Czechoslovakia when German troops, fighting off a ravaging snowstorm and vehicles’ technical problems, marched into Prague on March 15, 1939, and took over Bohemia and Moravia. (Earlier, at the Munich Conference in September of 1938, Hitler had acquired the Sudetenland region of Czechoslovakia.) While German citizens of the capital city saluted and waved swastika flags, some Czechs let out heartwrenching sobs while others displayed anger as they were horrified, overcome with powerlessness and hopelessness. Czechs hurled snowballs at the vehicles and refused to give lost Germans directions. Numerous Czechs gathered in Wenceslas Square, where they sang the national anthem. A photo of first democratic president Tomáš Garrigue Masaryk was placed on the Tomb of the Unknown Soldier, later destroyed by the Nazis, on Old Town Square. That day Hitler made his first and last visit to Prague. The next morning he signed a declaration that officially created the Nazi Protectorate of Bohemia and Moravia.

The Czech government and Nazi control

Germans in the country were automatically citizens of the Third Reich while Czechs had their own government, though the Nazis took over the ministries of defense, foreign affairs, communications, and customs. Clearly, the Third Reich was in control. Former democratic Czechoslovak president Eduard Beneš became the leader of the Czech government-in-exile, based in London. Slovakia became independent, supported by Nazi Germany, with Catholic priest Jozef Tiso as leader of a population that was 85 percent Slovak. Its political party was the Nazi-aligned Hlinka’s Slovak People’s Party – Party of Slovak National Unity as other political groupings were banned.

Suicides, shop windows, and the letter “V”

In response to the takeover, many chose suicide as a way out. Czechs had to possess new identification documents proclaiming they were not Roma or Jewish and had to show the authorities a family tree that went back to their grandparents’ era. Signs asserted that shops were Aryan; black-outs and rationing were the norm. People were trapped; no one could leave the Protectorate without a visa. Huge swastika-ridden flags hung from buildings as SS guards, ominously dressed in black, surveyed the streets. German officers and soldiers rode in cars decorated with swastikas. Hitler Youth parades were a common sight. After the Czechs painted the letter “V” for victory on buildings during a black-out as a show of resistance, the Nazis began to utilize the ”V” symbol for themselves. Soon, a huge “V” was created on the cobblestones of Old Town Square. Secondary schools received pro-Nazi textbooks. Many people were executed; the relatives of the deceased had to cover the costs of the execution and the posters announcing it.

The press, film, and artists against the regime

The press became propaganda for the Reich with books, music – such as jazz – and dramas also banned, but Czech films, cheerful comedies that served as a popular form of escape, were permitted as long as they were not nationalistic and had German subtitles. Reich Minister of Propaganda Joseph Goebbels even had the largest sound stage in Europe constructed in Prague. Political jokes were forbidden as was listening to a foreign radio station. Official radio broadcasts consisted of war news and concerts. There were illegal magazines in existence, too.

Many Czech artists emigrated. Jewish poet Jiří Orten became a victim of the regime when a German ambulance ran him over on September 1, 1940. Writer Vladislav Vančura was executed for his anti-Nazi views. Cubist painter and author Josef Čapek died in a concentration camp in 1945. By 1944, most museums and all theatres were closed.

Empty shops, overcrowded trams, and bad health

At the beginning of World War II, Prague shops were well-stocked with goods purchased before the war. Yet by 1944 stores were empty with signs proclaiming they were closed for the victory of the Reich. Garbage-ridden streets reeked. Nazi law forced people to drive on the right. By the end of 1944, private cars were banned. Most traveled on a bicycle or took dirty and crowded trams that often broke down. The tram stops were announced in both Czech and German.

By February of 1945, people found themselves working 64 hours per week and sometimes as many as 10 hours on Sundays. A lot of women opted to get pregnant so they would not have to toil in factories during the war. The demanding work week, poor diet, and illnesses brought on by stress all contributed to citizens’ bad health. Infectious diseases were also no strangers to the period. For leisure time, though, healthy people played sports such as ice hockey and went swimming. Horse racing was popular, too.

Czech resistance and Jan Opletal

Czechs took an active stance against the regime. There was an illegal Communist movement in the country, but many democrats also defied the Third Reich. One key event exhibiting resistance came on October 28, 1939, on the anniversary of the 1918 Czechoslovak independence day. Czechs boycotted newspapers infused with Nazi ideology and refused to ride trams because the stops were announced in both Czech and German. Demonstrations in Wenceslas Square and Old Town Square turned violent after Czechs tore down German signs. The German police’s open fire resulted in nine seriously wounded while 400 demonstrators were arrested. Medical student Jan Opletal, shot during the demonstration, died on November 11. The permitted funeral procession on November 15 was broken up by the Czech police. On November 17 nine student leaders were executed without trial. To punish the Czechs, Frank closed all Czech universities.

Czechs took an active stance against the regime. There was an illegal Communist movement in the country, but many democrats also defied the Third Reich. One key event exhibiting resistance came on October 28, 1939, on the anniversary of the 1918 Czechoslovak independence day. Czechs boycotted newspapers infused with Nazi ideology and refused to ride trams because the stops were announced in both Czech and German. Demonstrations in Wenceslas Square and Old Town Square turned violent after Czechs tore down German signs. The German police’s open fire resulted in nine seriously wounded while 400 demonstrators were arrested. Medical student Jan Opletal, shot during the demonstration, died on November 11. The permitted funeral procession on November 15 was broken up by the Czech police. On November 17 nine student leaders were executed without trial. To punish the Czechs, Frank closed all Czech universities.

The assassination of Heydrich and its aftermath

High-ranking official Reinhard Heydrich was the only leading Nazi assassinated during the war. On May 27, 1942, two Czech parachutists, sent by the Czech government-in-exile in London, hurled a bomb at his car while it slowed down at a sharp turn in Prague’s Libeň district. Heydrich died on June 4. In retaliation, the Nazis razed the villages of Lidice and Ležáky, shooting all the men, sending the women to concentration camps, and separating the parents from their children. A resistance fighter betrayed his colleagues, and the seven parachutists hiding in Prague’s Church of Saints Cyril and Methodius committed suicide rather than surrender to the German troops that had them surrounded. On July 3, 1942, the 200,000 Czechs gathered on Wenceslas Square were humiliated, forced to pledge their loyalty to the Reich and to give the Nazi salute.

High-ranking official Reinhard Heydrich was the only leading Nazi assassinated during the war. On May 27, 1942, two Czech parachutists, sent by the Czech government-in-exile in London, hurled a bomb at his car while it slowed down at a sharp turn in Prague’s Libeň district. Heydrich died on June 4. In retaliation, the Nazis razed the villages of Lidice and Ležáky, shooting all the men, sending the women to concentration camps, and separating the parents from their children. A resistance fighter betrayed his colleagues, and the seven parachutists hiding in Prague’s Church of Saints Cyril and Methodius committed suicide rather than surrender to the German troops that had them surrounded. On July 3, 1942, the 200,000 Czechs gathered on Wenceslas Square were humiliated, forced to pledge their loyalty to the Reich and to give the Nazi salute.

The annihilation of Jews in the Protectorate and Slovakia

During 1941 there were more than 90,000 Jews living in Bohemia and Moravia. Only a little over 14,000 survived the war. In September of 1941, Jews were forced to wear the yellow star. While the Germans destroyed synagogues and Jewish graveyards throughout the Sudetenland, they spared Prague the same fate because they planned to set up a Central Jewish Museum there with the property they had stolen from Jews who were deposited in overcrowded freight cars and sent to concentration camps.

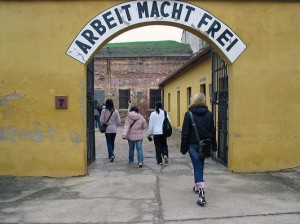

The first transport from Prague to Terezín, a Czech concentration camp and transit station for points farther east, took place in January of 1942. A total of 39,395 people were sent to Terezín, and 31,709 were killed. During the Red Cross inspection of Terezín in June of 1944, the three delegates were impressed with the flowerbed-flanked streets and theatre performances by the healthiest Jews.

The first transport from Prague to Terezín, a Czech concentration camp and transit station for points farther east, took place in January of 1942. A total of 39,395 people were sent to Terezín, and 31,709 were killed. During the Red Cross inspection of Terezín in June of 1944, the three delegates were impressed with the flowerbed-flanked streets and theatre performances by the healthiest Jews.

In Slovakia, a 270-paragraph long Jewish Codex limited the rights of Jews, proclaimed they must wear a yellow star, forbid intermarriage, and declared that Jewish property is repossessed by Aryans. Slovak Jews were expelled and gassed at concentration camps. Almost 80 percent of the Slovak pre-war population died during the war.

Air raids

Prague was for the most part preserved as there were only a few air raids. During the Valentine’s Day attack of 1945, which was carried out by Americans who mistook Prague for Dresden, a bridge, some buildings, and a hospital were destroyed with a death toll of over 400 and more than 1,400 wounded. Another raid in March sent over 500 people to their death.

The partisan movement in Slovakia

The partisan movement came to life both in Slovakia and in the Protectorate. The Slovak uprising took place in the fall of 1944. The Hlinka Guard, Slovakia’s pro-Nazi militia named after Catholic priest and Slovak politician Andrej Hlinka, who founded the fascist Slovak People’s Party, put off resistance fighters after the Russians crossed the Slovak border. During that spring the resistance group escaped into the mountains, and many died. Germans executed partisans and in September of that year, they obtained control of Slovakia, taking away its independence.

The Prague Uprising and the end of the war

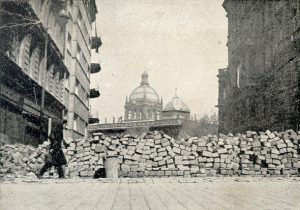

At the beginning of 1945, Praguers rebelled when Hitler threatened to annihilate the capital city. In early May the Prague Uprising took place as Czechs rebelled by destroying German street signs. Tram conductors would no longer accept German currency or announce stops in German. Czech flags fluttered from windows. The Germans tried to take control of Prague’s radio station, but after much fighting the Czechs were victorious. When Germans still did not give up, Czechs set up about 1,600 barricades. On May 8 the Germans retaliated by demolishing Prague’s Old Town Hall, its tower, and an astrological clock. Czech resistance fighters hanged Germans from lampposts and burned their bodies. A day earlier US General George S. Patton was ordered to stop at Pilsen as the Soviets arrived to free Prague on May 9, setting the country on a different, though just as bleak and dismal, a path that triggered 40 years of Communist terror.

At the beginning of 1945, Praguers rebelled when Hitler threatened to annihilate the capital city. In early May the Prague Uprising took place as Czechs rebelled by destroying German street signs. Tram conductors would no longer accept German currency or announce stops in German. Czech flags fluttered from windows. The Germans tried to take control of Prague’s radio station, but after much fighting the Czechs were victorious. When Germans still did not give up, Czechs set up about 1,600 barricades. On May 8 the Germans retaliated by demolishing Prague’s Old Town Hall, its tower, and an astrological clock. Czech resistance fighters hanged Germans from lampposts and burned their bodies. A day earlier US General George S. Patton was ordered to stop at Pilsen as the Soviets arrived to free Prague on May 9, setting the country on a different, though just as bleak and dismal, a path that triggered 40 years of Communist terror.