Petr Vok of Rožmberk: The Renaissance Cavalier of Český Krumlov

By Tracy A. Burns

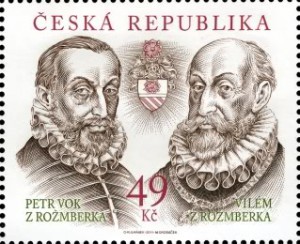

The last of the prominent Rožmberk (sometimes called Rosenberg) dynasty, Petr Vok of Rožmberk created magnificent Renaissance chateaus in Bechyně and Třeboň and influenced the development of Český Krumlov Castle, where he also spent his early childhood. His collection of artifacts and instruments was vast and extremely impressive. A Protestant nobleman during the Catholic Habsburg era of the Holy Roman Empire, he became the non-Catholic authority in the Czech lands.

The last of the prominent Rožmberk (sometimes called Rosenberg) dynasty, Petr Vok of Rožmberk created magnificent Renaissance chateaus in Bechyně and Třeboň and influenced the development of Český Krumlov Castle, where he also spent his early childhood. His collection of artifacts and instruments was vast and extremely impressive. A Protestant nobleman during the Catholic Habsburg era of the Holy Roman Empire, he became the non-Catholic authority in the Czech lands.

Childhood

Born at Český Krumlov Castle on October 1, 1539, his father was ruler Jošta III of Rožmberk, and his mother was Jošta III’s second wife, Anna of Rogendorf. His older brother, Vilém, would have a big influence on his life. Two weeks after Vok’s birth, his father died. His uncle, Petr V. of Rožmberk, was put in charge of the children and had a serious falling out with Vok’s mother. As a result, Vok’s uncle had to pay his mother a large sum of money. In return, she had to leave the Rožmberk domains and was not allowed to influence the education of her children. Vok was sent to his aunt’s place in Jindřichův Hradec at age three but then returned to Český Krumlov when his uncle died. His mother also was able to return to Krumlov. Vok was tutored at Český Krumlov Castle in subjects such as reading, Czech writing, religion, and Latin. According to a legend, the White Lady, the ghost of Perchta of Rožmberk, helped take care of Vok when he was a young child. Perchta had spent her happy childhood in Český Krumlov Castle, only to become trapped in a miserable marriage. She died at age 49 in 1476.

Growing up and the shift to Protestantism

When he grew up, Vok aspired to become independent. In 1557 Vok became acquainted with Jiří Arnošt of Henneberk, who was a devout Protestant. His passion for Lutheranism caught Vok’s attention. While not seeing eye-to-eye on religious matters with Emperor Ferdinand I, Vok did maintain a close relationship with the heir, Maximilian.

Travels through the Netherlands and England

During Maximilian II’s coronation as Roman king, Vok met Dutch Prince William of Orange, who thought he could manipulate Vok in order to forge a closer relationship with the future emperor. When Prince William of Orange invited Vok to the Netherlands, Vok enthusiastically accepted. He was enthralled with the high level of development in the Netherlands. During his travels there, he purchased many paintings and books. Later, he visited England for two weeks, when he met many members of royalty, including British Queen Elizabeth I. When he left England, the ship he was on almost capsized, but he managed to make it back to Český Krumlov safely in April of 1563.

Bechyně

Two years later Vilém gave three domains to his younger brother, enabling him to become independent. Vok then bought Bechyně and made his seat there, transforming its castle into a Renaissance jewel during the town’s golden age. He constructed three new residential wings and a tower above the entrance façade. Italian artists painted the courtyard and decorated the chateau’s courtroom, wedding hall, and armory with ornamental motifs.

Two years later Vilém gave three domains to his younger brother, enabling him to become independent. Vok then bought Bechyně and made his seat there, transforming its castle into a Renaissance jewel during the town’s golden age. He constructed three new residential wings and a tower above the entrance façade. Italian artists painted the courtyard and decorated the chateau’s courtroom, wedding hall, and armory with ornamental motifs.

Debts and conspiracies

Unfortunately, during the 1570s, Vok accrued large debts, and his subjects no longer had faith that he would repay them. People wanted him to be imprisoned until he could pay back the money he owed them. The tension with the serfs escalated to such a degree that his subjects planned to assassinate him or his noblemen. After rebels tried to kill one of his courtiers on two occasions, Vok severely punished the guilty and even executed three of the conspirators. However, that did not stop the serfs from revolting again. Fifty well-armed fishermen took a stand against Vok, who assembled an intricate surveillance team among several noble dynasties. All the conspirators were eventually caught, tortured, and executed. It is said that he executed so many that he had enough heads to fill a chest.

Marriage and the Bohemian Brethren

At age 40 on February 14, 1580, Vok married Kateřina of Ludanice, also a non-Catholic, at Bechyně Chateau. But his life was not rosy. Soon his relationship with his older brother became tense because Vok began practicing the Bohemian Brethren religion, which had been banned by the king. Vilém even threatened to take away Vok’s domains.

Paying back debts and moving to Třeboň

By this time, Vok had other troubles as well. Because of his huge debt, he had to sell some of his domains. He wound up selling Bechyně to the Šternberk clan in 1596 and between 1601 and 1602 sold Český Krumlov to Emperor Rudolf II. In 1601 his wife died and was buried in the Rožmberk family tomb at Vyšší Brod’s monastery in south Bohemia. Then Vok began residing in Třeboň, where he had extensive building carried out. Between 1605 and 1606, he built one of the most remarkable libraries in Europe and also was responsible for setting up a picture gallery and pharmacy at the chateau. New ponds were added to the property as well.

By this time, Vok had other troubles as well. Because of his huge debt, he had to sell some of his domains. He wound up selling Bechyně to the Šternberk clan in 1596 and between 1601 and 1602 sold Český Krumlov to Emperor Rudolf II. In 1601 his wife died and was buried in the Rožmberk family tomb at Vyšší Brod’s monastery in south Bohemia. Then Vok began residing in Třeboň, where he had extensive building carried out. Between 1605 and 1606, he built one of the most remarkable libraries in Europe and also was responsible for setting up a picture gallery and pharmacy at the chateau. New ponds were added to the property as well.

The threat of Passau

Then Passau came into the picture. Soldiers of the Bavarian town known for manufacturing swords invaded the Rožmberk domains by attacking Soběslav. They threatened to flood the entire Rožmberk property, and there was concern that the floods could reach as far as Prague. The Habsburgs sent soldiers prepared to fight, but Vok did not want any bloodshed. Instead, he agreed to pay Passau to keep the peace, but it was very difficult for him to come up with enough money.

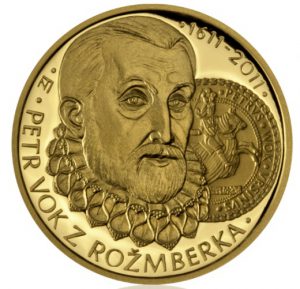

Death and funeral

Petr Vok passed away on November 6, 1611. A three-day funeral ensued with 24 knights carrying the coffin. Some 50 townspeople from the Rožmberk territory and some soldiers marched behind the coffin. A member of the Bohemian Brethren said mass at the Church of Saint Giles in Třeboň. Even though Vok had wanted to be buried in the Protestant church of Saint Jošt in Český Krumlov, he was interred at the family tomb near his wife in the Catholic church in Vyšší Brod.

Legacy

Jan Jiří of Švamberk inherited Vok’s property and also his many debts. Soon the Thirty Years’ War began, and Vok’s era was remembered as an idyllic, peaceful time. Two films deal with his life story while a play and opera have also been written about him. Biographies have been published, too. Even a literary prize has been named after him. In 2011 the Wallenstein Riding Stables Gallery in Prague hosted an extensive exhibition about the Rožmberk clan.