Prague Architecture – Guide to Architecture, part 1

Spellbinding Prague architecture from Romanesque through Historicism

Prague’s architecture is spellbinding. Many architectural gems from the Gothic, Renaissance, and Baroque era remain intact because the city was not rebuilt like most European capital cities during the 18th or 19th centuries when it was only a provincial town in the Austro-Hungarian Empire. Also, Prague was spared the tragic fate of cities such as Dresden during World War II. To be sure, Prague is a sort of “museum of architecture under the open sky.” The largest urban historical center listed on the UNESCO World Heritage List, this well-preserved area covers 900 hectares that include some 4,000 monuments.

Prague’s architecture is spellbinding. Many architectural gems from the Gothic, Renaissance, and Baroque era remain intact because the city was not rebuilt like most European capital cities during the 18th or 19th centuries when it was only a provincial town in the Austro-Hungarian Empire. Also, Prague was spared the tragic fate of cities such as Dresden during World War II. To be sure, Prague is a sort of “museum of architecture under the open sky.” The largest urban historical center listed on the UNESCO World Heritage List, this well-preserved area covers 900 hectares that include some 4,000 monuments.

Check out our thematic tour: Prague´s Architecture

Romanesque architecture

Spanning from before the year 800 to the 13th century, Romanesque architecture connected the ancient world with medieval times. It is characterized by round arches, thick walls, groin vaults, and large towers as well as symmetrical designs. The Romanesque style appeared in the Czech lands during the 9th century. The dominating structure of Romanesque architecture was the rotunda featuring a cylindrical nave of five to six meters with a conical roof. Some rotundas in Prague have been preserved up to the present day. In the Old Town, for instance, the rotunda of the Holy Cross still enthralls with fragments of 14th-century wall paintings in the nave. The New Town boasts the rotunda of Saint Martin at Vysehrad, which is the oldest rotunda in Prague. This Romanesque relic used to be a parish church during the 11th century. Long before it was a cathedral, Saint Vitus’ Cathedral at Prague Castle took the form of a rotunda but then was rebuilt as a basilica at the end of the 11th century. The remnants of Romanesque houses have been discovered in the basements of Old Town buildings, too. During the 12th century, these Romanesque creations consisted of stone residential buildings.

Gothic architecture

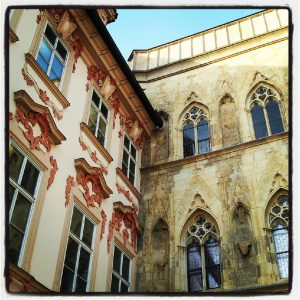

Gothic architecture made its appearance in Prague during the 13th century and consisted of pointed arches and flying buttresses. The dominating feature of Gothic architecture, however, is the ribbed vault, which featured pointed arches. The ribbed vault was popular because it was thinner, lighter, and more versatile than Romanesque stone vaults, which were very heavy. Most buildings were built with stone, especially sandstone. The Saint Agnes of Bohemia Convent is the oldest early Gothic complex in Bohemia and was built between 1233 and the late 1280s. The Old-New Synagogue is one of the best-preserved medieval synagogues in Europe and was erected around 1280. The tympanum of the entrance portal boasts stunning decoration. Introduced after 1300, High Gothic followed. It was the prevalent style during Luxembourg’s reign in the Czech lands. The House at the Stone Bell (Dum U Kamenneho zvonu), a former royal residence, is one example of this style. High Gothic was popular when Emperor Charles IV was on the throne. Gothic elements can still be seen in the Charles Bridge, the New Town, and Saint Vitus’ Cathedral, all of which Emperor Charles IV had built. St. Vitus Cathedral is the biggest church in Prague and home to the tombs of Bohemian kings as well as the crown jewels. The linear interiors feature little ornamentation, resembling French architecture of the 14th century. Still, the sculptural decoration of the cathedral is stunning. The statue of Saint Wenceslas and the gallery of portraits of Premyslid dynasty rulers are especially impressive. Then the Hussites wreaked much havoc during the Hussite wars of the 15th century. However, the Gothic style bounced back under the Jagellonian rulers. Prague Castle’s Vladislav Hall, constructed by Benedikt Ried at the end of the 15th century, is a Gothic delight featuring circular vaults. Yet the forms of the hall’s windows suggest the influence of the Italian Renaissance. Under this Gothic hall are the remains of a Romanesque stone palace built in 1135. Churches such as Our Lady before Tyn, Saint Nicholas Church in the Old Town, and Saint Nicholas Church in the Lesser Town all have Gothic cores, though they have all been rebuilt. The Carolinum, a complex of buildings founded by Charles IV in 1348 and now serving as the rectorate of Charles University, also had Gothic roots.

Gothic architecture made its appearance in Prague during the 13th century and consisted of pointed arches and flying buttresses. The dominating feature of Gothic architecture, however, is the ribbed vault, which featured pointed arches. The ribbed vault was popular because it was thinner, lighter, and more versatile than Romanesque stone vaults, which were very heavy. Most buildings were built with stone, especially sandstone. The Saint Agnes of Bohemia Convent is the oldest early Gothic complex in Bohemia and was built between 1233 and the late 1280s. The Old-New Synagogue is one of the best-preserved medieval synagogues in Europe and was erected around 1280. The tympanum of the entrance portal boasts stunning decoration. Introduced after 1300, High Gothic followed. It was the prevalent style during Luxembourg’s reign in the Czech lands. The House at the Stone Bell (Dum U Kamenneho zvonu), a former royal residence, is one example of this style. High Gothic was popular when Emperor Charles IV was on the throne. Gothic elements can still be seen in the Charles Bridge, the New Town, and Saint Vitus’ Cathedral, all of which Emperor Charles IV had built. St. Vitus Cathedral is the biggest church in Prague and home to the tombs of Bohemian kings as well as the crown jewels. The linear interiors feature little ornamentation, resembling French architecture of the 14th century. Still, the sculptural decoration of the cathedral is stunning. The statue of Saint Wenceslas and the gallery of portraits of Premyslid dynasty rulers are especially impressive. Then the Hussites wreaked much havoc during the Hussite wars of the 15th century. However, the Gothic style bounced back under the Jagellonian rulers. Prague Castle’s Vladislav Hall, constructed by Benedikt Ried at the end of the 15th century, is a Gothic delight featuring circular vaults. Yet the forms of the hall’s windows suggest the influence of the Italian Renaissance. Under this Gothic hall are the remains of a Romanesque stone palace built in 1135. Churches such as Our Lady before Tyn, Saint Nicholas Church in the Old Town, and Saint Nicholas Church in the Lesser Town all have Gothic cores, though they have all been rebuilt. The Carolinum, a complex of buildings founded by Charles IV in 1348 and now serving as the rectorate of Charles University, also had Gothic roots.

Renaissance

Influenced by ancient Greek and Roman culture and stressing symmetry and geometry, the Renaissance style first appeared in Florence during the 15th century. Large, comfortable, and light spaces helped define Renaissance structures. The horizontal was stressed in a simple form. Columns, pilasters, lintels, semicircular arches, and niches were characteristic of this trend. The style caught on in Prague during the end of that century. Not only did Vladislav Hall’s windows feature Renaissance elements, but the side portal of St. George’s Church, also at Prague Castle, took on a Renaissance look at that time. Built from 1538 to 1563, the Prague Castle royal summer palace was heralded as the first Renaissance structure in Prague. Its geometric garden featured exotic plants, and its bronze fountain, called the Singing Fountain, became one of the most prominent Renaissance sculptures in the Czech land. By the middle of the 16th century, the Renaissance style was in fashion. Houses and palaces promoted this style. For example, the house At the Two Golden Bears (U Dvou zlatých medvědů) and the Granovský house in the Old Town are Renaissance gems. The sgraffito-decorated Schwarzenberg Palace at Prague Castle is another example. Even when the Mannerist and Baroque styles came to the fore, the Renaissance style was not forgotten.

Influenced by ancient Greek and Roman culture and stressing symmetry and geometry, the Renaissance style first appeared in Florence during the 15th century. Large, comfortable, and light spaces helped define Renaissance structures. The horizontal was stressed in a simple form. Columns, pilasters, lintels, semicircular arches, and niches were characteristic of this trend. The style caught on in Prague during the end of that century. Not only did Vladislav Hall’s windows feature Renaissance elements, but the side portal of St. George’s Church, also at Prague Castle, took on a Renaissance look at that time. Built from 1538 to 1563, the Prague Castle royal summer palace was heralded as the first Renaissance structure in Prague. Its geometric garden featured exotic plants, and its bronze fountain, called the Singing Fountain, became one of the most prominent Renaissance sculptures in the Czech land. By the middle of the 16th century, the Renaissance style was in fashion. Houses and palaces promoted this style. For example, the house At the Two Golden Bears (U Dvou zlatých medvědů) and the Granovský house in the Old Town are Renaissance gems. The sgraffito-decorated Schwarzenberg Palace at Prague Castle is another example. Even when the Mannerist and Baroque styles came to the fore, the Renaissance style was not forgotten.

Baroque

Next in line was Baroque architecture, which featured monumental, dynamic effects and illusory elements. Other characteristics of this lavish style of innovative forms, light, and shadow include large-scale ceiling frescoes, broader naves in churches, the chiaroscuro effect, opulent ornamentation and pear-shaped domes. The name Baroque stems from the Italian “Barocco,” which means strange and peculiar. Large structures were made of brick, stone, or both and covered with thick layers of plaster. The movement was connected to the Counter-Reformation when the Catholic Church implemented internal reforms. Prague Baroque flourished, making quite a name for itself in Europe. Some buildings featuring early Baroque style are the Italian Chapel in the Clementinum Old Town Jesuit College and the Saint Ignacius Church on Charles Square in the New Town, which was built during the second half of the 17th century. The Matthias Gate at Prague Castle dates from 1614 and features a late Baroque passageway with a sail vault. The first and largest Baroque palace was the Wallenstein Palace in Lesser Town. Archbishop Jean-Baptist Mathey was the leading architect of Roman Baroque Classicism, which had its roots in Rome. Toskánský Palace, Troja Chateau, and the Church of St. Francis of Assisi are just three examples of his remarkable craftsmanship. Troja Chateau blends into the landscape of surrounding vineyards. Erected from 1679 to 1691, it is based on the design of a Roman summer villa. One significant feature is the exterior monumental staircase depicting the triumph of the gods of Olympus over the Titans. Sculptors Matthias Bernard Braun and Ferdinand Maxmilian Brokoff were prominent creators at the time, too. Painter Petr Brandl forged exquisite works. Going off on a tangent, Radical Baroque featured a refined spatial composition. Krystof Dientzhofer’s designs in this style graced the Czech lands. He was responsible for, among others, Saint Nicholas Church in the Lesser Town, which was given a Baroque look at the end of the 17th century. It took 50 years to build the Baroque jewel that includes a three-leaf chancel and 70-meter high dome created by Krystof’s son, Kilian Ignac Dientzenhofer. The interior was decorated by prominent Baroque artists, including painter Karel Skreta. The mastermind behind the Gothic Baroque was Jan Blažej Santini-Aichl, and one of his contributions in Prague is the façade and staircase of the Lesser Town’s Saint Kajetan Church. The Baroque tradition in architecture continued in the Czech lands even into the second half of the 18th century.

Next in line was Baroque architecture, which featured monumental, dynamic effects and illusory elements. Other characteristics of this lavish style of innovative forms, light, and shadow include large-scale ceiling frescoes, broader naves in churches, the chiaroscuro effect, opulent ornamentation and pear-shaped domes. The name Baroque stems from the Italian “Barocco,” which means strange and peculiar. Large structures were made of brick, stone, or both and covered with thick layers of plaster. The movement was connected to the Counter-Reformation when the Catholic Church implemented internal reforms. Prague Baroque flourished, making quite a name for itself in Europe. Some buildings featuring early Baroque style are the Italian Chapel in the Clementinum Old Town Jesuit College and the Saint Ignacius Church on Charles Square in the New Town, which was built during the second half of the 17th century. The Matthias Gate at Prague Castle dates from 1614 and features a late Baroque passageway with a sail vault. The first and largest Baroque palace was the Wallenstein Palace in Lesser Town. Archbishop Jean-Baptist Mathey was the leading architect of Roman Baroque Classicism, which had its roots in Rome. Toskánský Palace, Troja Chateau, and the Church of St. Francis of Assisi are just three examples of his remarkable craftsmanship. Troja Chateau blends into the landscape of surrounding vineyards. Erected from 1679 to 1691, it is based on the design of a Roman summer villa. One significant feature is the exterior monumental staircase depicting the triumph of the gods of Olympus over the Titans. Sculptors Matthias Bernard Braun and Ferdinand Maxmilian Brokoff were prominent creators at the time, too. Painter Petr Brandl forged exquisite works. Going off on a tangent, Radical Baroque featured a refined spatial composition. Krystof Dientzhofer’s designs in this style graced the Czech lands. He was responsible for, among others, Saint Nicholas Church in the Lesser Town, which was given a Baroque look at the end of the 17th century. It took 50 years to build the Baroque jewel that includes a three-leaf chancel and 70-meter high dome created by Krystof’s son, Kilian Ignac Dientzenhofer. The interior was decorated by prominent Baroque artists, including painter Karel Skreta. The mastermind behind the Gothic Baroque was Jan Blažej Santini-Aichl, and one of his contributions in Prague is the façade and staircase of the Lesser Town’s Saint Kajetan Church. The Baroque tradition in architecture continued in the Czech lands even into the second half of the 18th century.

Classicism

Featuring rationality, pragmatism, and simplicity, Classicism (also called Neo-Classicism) was inspired by the ideals of ancient Greece. Yet, while exteriors tended to be designed in Classicist style, the interiors often boasted lavish décor. While the number of churches and palaces decreased, there were more schools, hospitals, and administrative buildings erected in this style. Residential houses on the Smetana Waterfront exhibited these tendencies in Prague as did the newly-built suburb of Karlín, which featured a rational, systematic design. The Theatre of the Estates, constructed in 1783, has Baroque elements but is built in the Classicist tradition. All four walls of the theatre are symmetrical, each with a central section broken and crowned with a tympanum. The New Town Customs House exhibits elements of more modern styles as does the Governor’s Summer Palace above Stromovka Park. Historicism came to the fore in the second half of the 19th century.

Featuring rationality, pragmatism, and simplicity, Classicism (also called Neo-Classicism) was inspired by the ideals of ancient Greece. Yet, while exteriors tended to be designed in Classicist style, the interiors often boasted lavish décor. While the number of churches and palaces decreased, there were more schools, hospitals, and administrative buildings erected in this style. Residential houses on the Smetana Waterfront exhibited these tendencies in Prague as did the newly-built suburb of Karlín, which featured a rational, systematic design. The Theatre of the Estates, constructed in 1783, has Baroque elements but is built in the Classicist tradition. All four walls of the theatre are symmetrical, each with a central section broken and crowned with a tympanum. The New Town Customs House exhibits elements of more modern styles as does the Governor’s Summer Palace above Stromovka Park. Historicism came to the fore in the second half of the 19th century.

Historicism

Reproducing past styles with a fresh flair, historicism proved a momentous achievement in the 19th century. Religious buildings boasted Romanesque or Gothic styles. Theatre and museums were designed in Renaissance form. In Vienna, the Historical Style blossomed, celebrating the rise of the Austrian Empire and the richness of Austrian culture. Historical-style buildings in Prague celebrated the great influence of Czech society. Such creations include the National Theatre and Rudolfinum, planned by architects Josef Zítek and Josef Schultz, who also helped create the National Museum on Wenceslas Square. The National Theatre is decorated with Roman chariots on a pedestal of the main façade. The National Museum’s exterior includes a three-flight staircase with a fountain. The entrance has a tympanum above the main cornice and is topped with a tower covered by a dome on a square base with a 70-meter high lantern. Saint Vitus’ Cathedral was finished in Gothic style. The streets no longer sported a medieval appearance. Prague became a modern, capital city. Many historical houses were demolished. In the Old Town and the Jewish Quarter, 600 Gothic, Baroque, and Renaissance buildings were torn down to make way for apartment buildings.

Reproducing past styles with a fresh flair, historicism proved a momentous achievement in the 19th century. Religious buildings boasted Romanesque or Gothic styles. Theatre and museums were designed in Renaissance form. In Vienna, the Historical Style blossomed, celebrating the rise of the Austrian Empire and the richness of Austrian culture. Historical-style buildings in Prague celebrated the great influence of Czech society. Such creations include the National Theatre and Rudolfinum, planned by architects Josef Zítek and Josef Schultz, who also helped create the National Museum on Wenceslas Square. The National Theatre is decorated with Roman chariots on a pedestal of the main façade. The National Museum’s exterior includes a three-flight staircase with a fountain. The entrance has a tympanum above the main cornice and is topped with a tower covered by a dome on a square base with a 70-meter high lantern. Saint Vitus’ Cathedral was finished in Gothic style. The streets no longer sported a medieval appearance. Prague became a modern, capital city. Many historical houses were demolished. In the Old Town and the Jewish Quarter, 600 Gothic, Baroque, and Renaissance buildings were torn down to make way for apartment buildings.

The reconstruction of Prague’s Jewish Quarter

The Jewish Town suffered immensely during the clearance project that took place from 1896 to 1912. The quarter was riddled with problems – a high death rate, low hygienic standards, and overpopulation in a dense area. The plan for redevelopment was approved in 1893 and affected 380,000 square meters or some 600 buildings. The Prague City Council began demolishing buildings in the Jewish Town in 1895 and a year later raised the level of the ground, installed drinking water mains, and building-wide streets. The narrow, maze-like streets of the Jewish Town disappeared. By 1912 only six synagogues, the Old Jewish Cemetery, and the Jewish Town Hall were proof that the Jewish Town had ever existed.

The Jewish Town suffered immensely during the clearance project that took place from 1896 to 1912. The quarter was riddled with problems – a high death rate, low hygienic standards, and overpopulation in a dense area. The plan for redevelopment was approved in 1893 and affected 380,000 square meters or some 600 buildings. The Prague City Council began demolishing buildings in the Jewish Town in 1895 and a year later raised the level of the ground, installed drinking water mains, and building-wide streets. The narrow, maze-like streets of the Jewish Town disappeared. By 1912 only six synagogues, the Old Jewish Cemetery, and the Jewish Town Hall were proof that the Jewish Town had ever existed.