Prague Spring, 1968

By Erin Naillon

At the beginning of 1968, a breath of fresh air blew into Czechoslovakia when Alexander Dubček was elected First Secretary of the Communist Party of Czechoslovakia.

The Stalin era had had a profound impact on the Iron Curtain countries, and a process is known as “de-Stalinization” had been going on for some years, ever since Stalin’s death in 1953. Life was not as hard as it had been, and more than a few citizens wanted a much better life for themselves. Antonín Novotný was in charge at the time, and he found himself losing popular support, even though he had instituted various reforms. On January 5, 1968, Dubček replaced Novotný as First Secretary. On March 22 of that year, Novotný resigned as President.

Changes Begin

In February of 1968, Dubček made a speech emphasizing the need for reforms. True to his word, in April, he instituted greater freedom of speech, the press, and movement. He believed that Czechoslovakia should be divided into two countries; he also spoke of the need to limit the power of the secret police. He foresaw a period of ten years bridging the gap between things as they were and the ultimate goal of democratic socialism. It was a startling announcement.

Reactions Abroad

Not surprisingly, Brezhnev did not approve of Dubček’s plan for reform. After all, in 1956, Hungary had experienced an uprising against Soviet-implemented regulations. At first, the Soviet Union attempted to negotiate Dubček out of his decisions. Meetings took place in Slovakia in July and August, during which Dubček stated his support for the Warsaw Pact. Concessions were made on both sides, and the Bratislava Declaration was signed on August 3. Ominously, the Soviet Union expressed its intent to invade any Warsaw Pact member state that showed signs of returning to a capitalist system.

August 1968

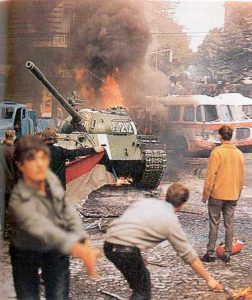

On August 20 – 21, Soviet tanks rolled into Czechoslovakia. Additional troops were provided by Poland, Bulgaria, and Hungary (though Hungary’s leader had originally voiced his support for Dubček’s election). Word got out that the invasion was taking place, and the country went into action. Signs showing the names of towns and cities were quickly taken down and replaced by signs reading “Dubček.” Others simply pointed the way back to Moscow. Eventually, the troops made their way to Prague and took over the airport.

On August 20 – 21, Soviet tanks rolled into Czechoslovakia. Additional troops were provided by Poland, Bulgaria, and Hungary (though Hungary’s leader had originally voiced his support for Dubček’s election). Word got out that the invasion was taking place, and the country went into action. Signs showing the names of towns and cities were quickly taken down and replaced by signs reading “Dubček.” Others simply pointed the way back to Moscow. Eventually, the troops made their way to Prague and took over the airport.

Death and Protest

Seventy-two people died in the invasion; another 702 were injured, some seriously. Protests were held on Prague’s Wenceslas Square. Nicolae Ceaşescu gave a public speech condemning the invasion. A protest demonstration was held in Helsinki, Finland. Even in Moscow itself, demonstrators dared to voice their opposition to the invasion of Red Square. (They were all arrested.) Dubček himself had been arrested and taken to Moscow, where he was forced to sign the Moscow Protocol.

1969

In 1969, Dubček’s career changed dramatically, from politician to forestry worker. His reforms were abolished, and it was business as usual under Communism. University student Jan Palach set himself on fire at the top of Wenceslas Square; this suicide was followed by two more in 1969 (Jan Zajíc and Evžen Plocek).

1989

Prague Spring, and especially the suicide of Jan Palach, had repercussions much later. Palach became something of a folk hero, and demonstrations in memory of his death 20 years later grew into protests against the Communist regime. These 1989 demonstrations, known as Palach Week, helped to create an atmosphere of liberal reform that helped to topple the government in November of that year. Dubček, the man who had advocated “Communism with a human face,” now found himself working in politics again, under the new President of Czechoslovakia, Václav Havel (one of those dissidents who had caused the regime so much trouble in the past). Dubček died in 1992.