Přemysl Otakar II: The Iron and Golden King

By Tracy A. Burns

Dubbed The Iron and Golden King, Přemysl Otakar II brought prosperity and prestige to the Czech lands as the fifth Czech leader, ruling from 1253 to 1278. With the exception of Holy Roman Emperor Charles IV, this energetic and well-educated ruler is the most revered Czech sovereign due to his penchant for promoting trade as well as making legal and other reforms.

Dubbed The Iron and Golden King, Přemysl Otakar II brought prosperity and prestige to the Czech lands as the fifth Czech leader, ruling from 1253 to 1278. With the exception of Holy Roman Emperor Charles IV, this energetic and well-educated ruler is the most revered Czech sovereign due to his penchant for promoting trade as well as making legal and other reforms.

Creating towns

One of the most significant achievements in his career involved creating about 50 towns in Bohemia, Moravia, Silesia, Austria, and Styria. The Bohemian king founded Prague’s Lesser Quarter (today’s Malá Strana) plus important Czech centers such as southern Bohemia’s České Budějovice and Písek, where the oldest standing bridge in the Czech lands and the second oldest in central Europe was built during the 1260s. Northern Bohemia’s Ústí nad Labem and central Bohemia’s Mělník, Kutná Hora and Nymburk were born as well. In Moravia Otakar II established Olomouc, Uherské Hradiště and Uherský Brod, among others. In lower Austria, Marchegg came into existence. Königsberg was bulit in what was then Prussia. Otakar II provided these new settlements with civic charters that bestowed privileges, such as the right to brew beer. He made sure that Jews were treated as members of Czech society, granting them privileges as far back as 1254, including the right to protect their property. The Czech protector of peace encouraged German speakers to make their homes in Czech towns and convinced them to move into Prague’s Lesser Quarter.

One of the most significant achievements in his career involved creating about 50 towns in Bohemia, Moravia, Silesia, Austria, and Styria. The Bohemian king founded Prague’s Lesser Quarter (today’s Malá Strana) plus important Czech centers such as southern Bohemia’s České Budějovice and Písek, where the oldest standing bridge in the Czech lands and the second oldest in central Europe was built during the 1260s. Northern Bohemia’s Ústí nad Labem and central Bohemia’s Mělník, Kutná Hora and Nymburk were born as well. In Moravia Otakar II established Olomouc, Uherské Hradiště and Uherský Brod, among others. In lower Austria, Marchegg came into existence. Königsberg was bulit in what was then Prussia. Otakar II provided these new settlements with civic charters that bestowed privileges, such as the right to brew beer. He made sure that Jews were treated as members of Czech society, granting them privileges as far back as 1254, including the right to protect their property. The Czech protector of peace encouraged German speakers to make their homes in Czech towns and convinced them to move into Prague’s Lesser Quarter.

Legal reforms and economic success

Czech law has a solid foundation thanks to Otakar II’s ingenious legal system that created many new principles. In fact, the Zemské desky, the oldest preserved source concerning Czech law, came into existence during his reign. Otakar II also helped the mining town of Jihlava in Moravia become a source of silver riches for the Czech lands. During his reign, the kingdom did not experience financial problems, either.

Castle building flourishes

Castle building flourished under Otakar II’s reign. During the second half of the 13th century, southern Bohemia’s Zvíkov became extremely powerful. Southern Bohemia’s Orlík, Hluboká nad Vltavou and Jindřichův Hradec also came into existence. Křivoklat Castle in central Bohemia and Bezděz Castle in northern Bohemia were constructed, too. Yet Otakar II’s construction of fortified palaces was not limited to the Czech lands. The Hofburg Palace in Vienna was built during his reign, too. He also established monasteries, such as the southern Bohemian jewel of Zlatá Koruna, then called Trnova Koruna, during 1263.

Fate intervening

The second son of King Wenceslas (Václav) I, Otakar II was born around 1233 and did not seem destined for the throne. He planned to focus on religion, but when his older brother Vladislav died in 1247, fate intervened.

A tense father-son relationship

Otakar II and Wenceslas I did not have a thriving father-son relationship, to say the least. In fact, the son led nobles in an uprising against the monarch, earning him the name “The Younger King.” Wenceslas triumphed over his son and sent Otakar II to prison for a few weeks. However, the good-looking, extrovert Otakar II was heir to the throne, and his father had a change of heart. When Wenceslas I sent his troops into the leaderless Duchy of Austria, Otakar II helped him. In 1251 Otakar II obtained the titles of Margrave of Moravia and Duke of Austria.

First marriage

The Czech ruler married for political reasons, hoping to strengthen the Přemysl domains in Europe. On February 11, 1251, at the age of 19, he wed the late Holy Roman Emperor Frederick II’s sister Margaret (Markéta), a 47-year-old, sickly widow.

Becoming king and Czech-Hungarian clashes

When King Wenceslas died in 1253, Otakar II donned the crown, and the admirable fighter expanded his kingdom. His cousin, King Béla IV of Hungary, frowned up Otakar’s successes and tried to obtain the Duchy of Styria, which had belonged to Austria since the end of the 12th century. This Czech-Hungarian clash proved the first of many bloody arguments between the two rulers. This time the Pope moderated, deciding that Béla would obtain much of Styria but Otakar would possess the rest of Austria. Still not satisfied, King Bela IV waged war with the Bohemian king again. Otakar II triumphed over his cousin at the Battle of Kressenbrunn during 1260.

Second marriage

It was also at this time that Otakar’s marriage with Margaret fell apart. Leaving her, Otakar II took Béla IV’s granddaughter, Kunigunda of Slavonia, who descended from a Russian dynasty, as his new, young wife on October 25, 1261. While his marriage to Margaret had been childless, with Kunigunda he produced four children: Henry, who died at a very young age; Kunigunde of Bohemia (1265-1321); Agnes of Bohemia (1269-1296); and his only legitimate son, Wenceslas II (1271-1305). He also had two illegitimate sons and some daughters.

Expanding his kingdom

Otakar’s kingdom became larger and larger as he waged war with Prussia as well as inherited Carinthia and a section of Carniola. Hungarian-Czech wars riddled the 1270s, during the reign of Hungarian King Stephen V. From 1273 to 1276 even Bratislava was under Otakar’s control. Despite his successes, he was not elected as the Imperial German ruler, as he bid for the position a second time in 1273. Rudolf of Habsburg received that honor, and Otakar II perceived him to be weak and inefficient.

Doing battle with Rudolf of Habsburg

He couldn’t have been more wrong. In 1274 Rudolf claimed back all the lands that had belonged to Holy Roman Emperor Frederick II as far back as 1245. Otakar II worried he would be stripped of Styria, Austria, and Corinthia. Two years later, Rudolf attacked Vienna, and in November of 1276, Rudolf persuaded Otakar II to sign a treaty stating that he would surrender all his lands except for Bohemia and Moravia.

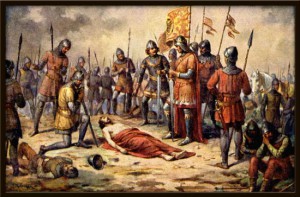

August 26, 1278, and the Battle of the Marchfield

Otakar II tried to strengthen his political stance with Rudolph by engaging his son Wenceslas II with Rudolph’s daughter Judith. Far from satisfied with the treaty and eager to get back the lands he had lost, Otakar II went to battle with Rudolph again. However, Hungary came to Rudolph’s aid, overpowering Otakar’s impressive army. Otakar II went down fighting at the Battle of the Marchfield on August 26, 1278, as a golden era in Czech history came to an abrupt and tragic halt. Yet, prosperous times would return when Wenceslas II became ruler of a kingdom that extended from the Baltic Sea to the Danube River. Like his father, he would establish many towns.

Otakar II tried to strengthen his political stance with Rudolph by engaging his son Wenceslas II with Rudolph’s daughter Judith. Far from satisfied with the treaty and eager to get back the lands he had lost, Otakar II went to battle with Rudolph again. However, Hungary came to Rudolph’s aid, overpowering Otakar’s impressive army. Otakar II went down fighting at the Battle of the Marchfield on August 26, 1278, as a golden era in Czech history came to an abrupt and tragic halt. Yet, prosperous times would return when Wenceslas II became ruler of a kingdom that extended from the Baltic Sea to the Danube River. Like his father, he would establish many towns.

A casket for a king

Rudolph put Otakar II’s casket on display in Vienna before it was moved to a monastery in Znojmo, Moravia. The coffin, which contained Otakar’s crown and scepter, was transferred to Prague in 1296 but was not placed in Saint Vitus’ Cathedral until 1373. Renowned German architect Pert Parléř made the headstone that he decorated with a sculpture of a knight in heavy armor, clad in a royal garment and donning a crown. Parléř is also known for designing Prague’s Charles Bridge and for helping design Prague Castle’s Saint Vitus Cathedral.

Přemysl Otakar II in art and literature

The character Přemyslid Otakar II appears in artwork and literature throughout the world. Decorative artist Alphonse Mucha immortalized Otakar II in his Slav Epic series of paintings. One canvas, called “Přemysl Otakar II: The Union of Slavic Dynasties,” possesses a sharp contrast of light and dark and is rich in a red wine hue. It depicts the Czech king celebrating his niece’s wedding while gathering with other Slavic leaders. In Dante’s The Divine Comedy, Otakar II is visible outside the gates of Purgatory, passing the time with his real-life rival, Rudolph of Habsburg. The time period immediately following Otakar II’s death is portrayed by Bedřich Smetana in his opera The Brandenburgers in Bohemia. The revered member of the Přemysl dynasty is the protagonist in the 1977 Czech novel Iron King, Golden King by Ludmila Vaňková, and this author focuses on the era following Otakar’s death in another book. The 19th-century Austrian Franz Grillparzer wrote a play about the legendary ruler, too. Likewise, Otakar II is the main character of a drama by the 16th and 17th-century Spanish playwright and poet Lope de Vega.