September 30, 1938: The Munich Agreement

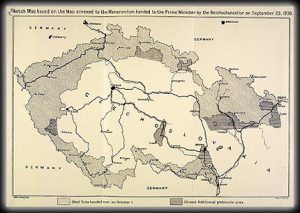

When Germany, France, Britain and Italy signed the Munich Agreement in the early hours of September 30, 1938, the Nazis took over Czechoslovakia’s Sudetenland, where mostly ethnic Germans lived along the Czech borders. The treaty also enabled Germany to take over Czechoslovakia, which they did officially on March 15, 1939. Notably, Czechoslovakia was not represented at the conference that decided that country’s fate. The agreement is viewed in hindsight as a failed attempt to avoid war with Nazi Germany.

The Sudeten Germans speak out

After World War I, borders had been drawn within the former Austro-Hungarian Empire, and these borders had triggered resentment and local conflicts. The German minority in post-World War I Czechoslovakia had yearned to become independent, not satisfied with its status in Czechoslovakia between the wars. When Germany annexed the Sudetenland, the majority of the 3.5 million Germans living there were ecstatic. By 1935 Konrad Henlein, a Sudeten German himself had built his pro-Nazi Sudetenland German Party (SDP) into the second largest political party in Czechoslovakia. Much friction evolved between the government and the party when the Czechoslovak administration blatantly refused to give the Sudetenland autonomy, one of its demands in the Carlsbad Program. In 1938, Adolf Hitler supported the Sudeten Germans’ desire to build a close relationship with Germany. Hitler aspired to aid the Sudeten Germans and destroy Czechoslovakia.

After World War I, borders had been drawn within the former Austro-Hungarian Empire, and these borders had triggered resentment and local conflicts. The German minority in post-World War I Czechoslovakia had yearned to become independent, not satisfied with its status in Czechoslovakia between the wars. When Germany annexed the Sudetenland, the majority of the 3.5 million Germans living there were ecstatic. By 1935 Konrad Henlein, a Sudeten German himself had built his pro-Nazi Sudetenland German Party (SDP) into the second largest political party in Czechoslovakia. Much friction evolved between the government and the party when the Czechoslovak administration blatantly refused to give the Sudetenland autonomy, one of its demands in the Carlsbad Program. In 1938, Adolf Hitler supported the Sudeten Germans’ desire to build a close relationship with Germany. Hitler aspired to aid the Sudeten Germans and destroy Czechoslovakia.

Pressure from Britain, France, and Germany

While France and the USA were set on avoiding war, Britain supported the Sudeten Germans’ plight. Czechoslovakia relied heavily on support from Britain and France, but they did not receive any. On the contrary, Britain and France pressured Czechoslovakia to yield to the Sudeten Germans’ demands. However, the Czechoslovak government was not to be swayed. Czechoslovak President Edvard Beneš even mobilized the army. Because the Germans wanted the Western Powers to abandon the Czechs, they had fictitious accounts of Czechs abusing Germans published in the press that August, the same month that Germany placed 750,000 soldiers along the Czechoslovak border.

Compromise and a resounding “no”

President Beneš realized that he had to compromise. He gave in to the Fourth Plan, which enforced almost all the German demands. But the Sudeten Germans would not give an inch, backing Hitler when he claimed that the Czechoslovak government wanted to exterminate all Sudetens. The German-speaking minority held demonstrations that the police had to break up. When British Prime Minister Neville Chamberlain, intent on avoiding war, met with Hitler, the Reich leader did not budge. Rather, he insisted that the Sudetenland become part of Germany. In the end, France and Britain gave the Czechoslovaks an ultimatum: cede all the territories with a German population of 50 percent or higher to the Reich in return for the security of knowing Czechoslovakia would remain independent. Czechoslovakia replied with a resounding “no.”

President Beneš realized that he had to compromise. He gave in to the Fourth Plan, which enforced almost all the German demands. But the Sudeten Germans would not give an inch, backing Hitler when he claimed that the Czechoslovak government wanted to exterminate all Sudetens. The German-speaking minority held demonstrations that the police had to break up. When British Prime Minister Neville Chamberlain, intent on avoiding war, met with Hitler, the Reich leader did not budge. Rather, he insisted that the Sudetenland become part of Germany. In the end, France and Britain gave the Czechoslovaks an ultimatum: cede all the territories with a German population of 50 percent or higher to the Reich in return for the security of knowing Czechoslovakia would remain independent. Czechoslovakia replied with a resounding “no.”

More demands from Hitler

Finally, on September 21, Czechoslovakia agreed to the demands promoted by Britain, France, and Germany. A few days earlier, the leader of the Italian National Fascist Party Benito Mussolini had lent his support to Nazi Germany. Yet Hitler made more demands, this time concentrating on the ethnic Germans in Poland and Hungary. When Chamberlain met Hitler in Germany again, Hitler did not mince words. He wanted to destroy Czechoslovakia and the Czechs. Later, though, Hitler agreed to annex only the Sudetenland and not to trespass into any other realms if Czechoslovakia started to evacuate its German speakers by October 1.

Signing the Munich Agreement

The Czechoslovaks wanted to go down fighting and mobilized the army. A quarter of a million dissatisfied Czechs rallied in front of Prague’s Rudolfinum concert hall, where high-ranking Communist official Klement Gottwald addressed them. France also began to mobilize its troops in the event of what looked like an impending war. President Beneš refused to instigate a war without the Western Powers backing him up. Although Hitler had demanded that Czechoslovakia cede the Sudetenland by September 28 or war would break out, the Munich Agreement was not signed until 1:30 a.m. on September 30, though it was dated September 29. The signatories were Hitler, Britain’s Chamberlain, France’s Prime Minister Édouard Daladier, and Italy’s Mussolini. The Sudetenland would join the Reich by October 10, and the fate of other territories would be decided by an international commission. Britain and France put their foot down and told Czechoslovakia that they would have to fight Germany alone or act according to the Munich Agreement.

The Czechoslovaks wanted to go down fighting and mobilized the army. A quarter of a million dissatisfied Czechs rallied in front of Prague’s Rudolfinum concert hall, where high-ranking Communist official Klement Gottwald addressed them. France also began to mobilize its troops in the event of what looked like an impending war. President Beneš refused to instigate a war without the Western Powers backing him up. Although Hitler had demanded that Czechoslovakia cede the Sudetenland by September 28 or war would break out, the Munich Agreement was not signed until 1:30 a.m. on September 30, though it was dated September 29. The signatories were Hitler, Britain’s Chamberlain, France’s Prime Minister Édouard Daladier, and Italy’s Mussolini. The Sudetenland would join the Reich by October 10, and the fate of other territories would be decided by an international commission. Britain and France put their foot down and told Czechoslovakia that they would have to fight Germany alone or act according to the Munich Agreement.

Consequences of the Munich Agreement: Czechoslovakia ceased to exist

By December of 1938, the Sudetenland was the most pro-Nazi region in the Reich as half a million Sudeten Germans had taken membership in the Nazi Party. Daladier was convinced that the agreement would not appease the Nazis and that disaster was yet to come while Chamberlain thought there was cause for celebration, mistakenly convinced that he had achieved peace. The day after the agreement was signed Germany took over the Sudetenland. The Czechoslovaks did not retaliate. On March 15, 1939, Hitler occupied Bohemia and Moravia, and Czechoslovakia ceased to exist. Slovakia had become an autonomous Nazi puppet state a day earlier. Many Sudeten Germans acquired jobs in the Protectorate or as Gestapo agents because they were fluent in Czech. Northern Ruthenia, hoping for independence, was taken over by Hungary.

By December of 1938, the Sudetenland was the most pro-Nazi region in the Reich as half a million Sudeten Germans had taken membership in the Nazi Party. Daladier was convinced that the agreement would not appease the Nazis and that disaster was yet to come while Chamberlain thought there was cause for celebration, mistakenly convinced that he had achieved peace. The day after the agreement was signed Germany took over the Sudetenland. The Czechoslovaks did not retaliate. On March 15, 1939, Hitler occupied Bohemia and Moravia, and Czechoslovakia ceased to exist. Slovakia had become an autonomous Nazi puppet state a day earlier. Many Sudeten Germans acquired jobs in the Protectorate or as Gestapo agents because they were fluent in Czech. Northern Ruthenia, hoping for independence, was taken over by Hungary.

More consequences of the agreement

Dismayed by the betrayal of his Western allies, President Beneš resigned on October 5, 1939, and soon fled to London, where he set up a government-in-exile. In the First Vienna Award of November 1938, Germany and Italy made Czechoslovakia hand over southern Slovakia and southern Ruthenia to Hungary while Poland took over the town of Český Těšín and the surroundings as well as two regions of northern Slovakia.

Refugees, Karel Čapek, and more

Not every German was enthusiastic about living in the Reich, however. Before the Occupation, approximately 30,000 Germans and 115,000 Czechs fled to the interior of Czechoslovakia. When well-renowned writer Karel Čapek, who fervently supported democratic ideals, died on December 25, 1938, Prague’s National Theatre refused to raise a black flag in his honor. After the Protectorate of Bohemia and Moravia was created, the Communist Party was banned and stripped of its property. Communists were expelled from Parliament, too. The Liberated Theatre, which performed anti-fascist productions courtesy of the ingenious duo of actors Jiří Voskovec and Jan Werich, was shut down.

War erupts

After Germany invaded Poland on September 1, 1939, Chamberlain declared war on the Nazis. World War II had begun. It is noteworthy that Britain and France entered the war over Danzig. One could argue that it made more sense to depend on an independent nation like Czechoslovakia than to deny Germany a corridor to East Prussia. Perhaps they realized that Hitler would stop at nothing.

The Beneš decrees

After the war, Czechoslovak President Beneš enforced his so-called Beneš decrees, which declared that Germans, Hungarians, traitors, and collaborators living in the Czech lands and Slovakia would have to give up their Czechoslovak citizenship and their property without compensation. Furthermore, approximately three million ethnic Germans and Hungarians were expelled from the country from 1945 to 1947. Some 19,000 Germans met their deaths in the process of moving, and another 6,000 were murdered. The controversial Beneš decrees are still in force today, causing much tension within the Czech Republic and abroad. Read more about the Benes decrees.