Terezin Concentration Camp – Theresienstadt

By Tracy A. Burns

History of Terezin – Theresienstadt

Terezín existed long before it became a Nazi work camp with a Gestapo prison during World War II. Because it was easily accessible and easy to guard, the Austrians used it to strengthen their defense system against the Prussians. Terezín, built from 1780 to 1790, was named by Emperor Joseph II after his mother, Empress Maria Theresa. Yet no battles took place there. Later, in the 19th century, the fortress also served as a prison. During World War I, it held political prisoners, including Bosnian Serb Gavrilo Princip, who killed Archduke Franz Ferdinand and his wife on June 28, 1914. The town is today divided into the small fortress (a Gestapo prison from 1941 to 1945) and the former ghetto from the Nazi era, where the Ghetto Museum and other sights are located.

Terezín existed long before it became a Nazi work camp with a Gestapo prison during World War II. Because it was easily accessible and easy to guard, the Austrians used it to strengthen their defense system against the Prussians. Terezín, built from 1780 to 1790, was named by Emperor Joseph II after his mother, Empress Maria Theresa. Yet no battles took place there. Later, in the 19th century, the fortress also served as a prison. During World War I, it held political prisoners, including Bosnian Serb Gavrilo Princip, who killed Archduke Franz Ferdinand and his wife on June 28, 1914. The town is today divided into the small fortress (a Gestapo prison from 1941 to 1945) and the former ghetto from the Nazi era, where the Ghetto Museum and other sights are located.

Prisoners in the Terezin´s small fortress

Throughout the five years, some 32,000 prisoners went through the camp and were often then deported to other camps farther East, where they met their deaths. Some 3,000 of them were foreigners – from Russia, Poland, and France, for instance. Approximately 2,500 inmates died in the small fortress. A sub-camp also existed in nearby Litoměřice, where conditions were also harsh. The Nazis needed the small fortress because the existing prisons were full, and they were arresting many resistance fighters and communists early during the war. Those who aided resistance workers, people who committed sabotage, and Jews who broke anti-Semitic laws were also inmates at that time.

Throughout the five years, some 32,000 prisoners went through the camp and were often then deported to other camps farther East, where they met their deaths. Some 3,000 of them were foreigners – from Russia, Poland, and France, for instance. Approximately 2,500 inmates died in the small fortress. A sub-camp also existed in nearby Litoměřice, where conditions were also harsh. The Nazis needed the small fortress because the existing prisons were full, and they were arresting many resistance fighters and communists early during the war. Those who aided resistance workers, people who committed sabotage, and Jews who broke anti-Semitic laws were also inmates at that time.

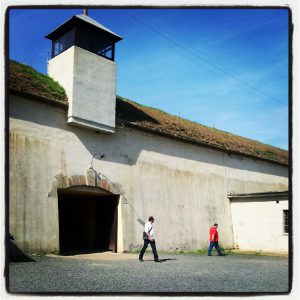

The first courtyard

There are four prisoners’ courtyards at the small fortress. In the first courtyard for men, roll call took place in the morning and evening. Visitors can see 17 cells. Each small space was used for 60 to 90 people. Wooden planks made up bunk beds that were three tiers high. There was one toilet and one sink, and water had to be reused. Lice and insects contributed to the bad hygiene.

The second courtyard

The second courtyard

The second courtyard was devoted to administrative procedures, which included torture. Prisoners received old Czechoslovak army uniforms in the Storage Room, while women kept their civilian attire. On the breast and back of the shirts was a yellow star if the inmate was Jewish or triangles denoting various categories. The incarcerated also received clogs, a blanket, a metal bowl, and a spoon, and all men were shaved bald.

Cells for Jews

While Jews were usually gathered in the adjacent ghetto, the ones who had tried to escape from there or were involved in the resistance were sent to the small fortress for a brutal punishment. Imagine 60 prisoners crammed into a small space with no toilet, no light, no fresh air, and no seating.

The third and fourth courtyards

The third and fourth courtyards

In the fourth courtyard, built-in 1943, huge cells held from 400 to 600 people. Up to 20 people were held in each of the 125 solitary confinement cells, which did not have toilets or heating. The third courtyard, reserved for women, now houses exhibitions.

The shower room, sick bay, and more

There are also 20 solitary confinement cells, and Princip died in cell number one after a four-year stay. A central shower room with a delousing station for clothes was set up in 1943. After the 100 or so inmates showered together, they had to wear their wet clothes. Sickbay, set up in 1940, originally had only eight beds. The former hospital, which was used only once, now houses an exhibition of Milada Horáková, a political prisoner who wound up being executed by the Communists in 1950. About 2,600 people died in prison from 1940 to 1945. During the last weeks of the war, spotted fever and typhoid epidemics ravaged the camp.

There are also 20 solitary confinement cells, and Princip died in cell number one after a four-year stay. A central shower room with a delousing station for clothes was set up in 1943. After the 100 or so inmates showered together, they had to wear their wet clothes. Sickbay, set up in 1940, originally had only eight beds. The former hospital, which was used only once, now houses an exhibition of Milada Horáková, a political prisoner who wound up being executed by the Communists in 1950. About 2,600 people died in prison from 1940 to 1945. During the last weeks of the war, spotted fever and typhoid epidemics ravaged the camp.

The execution grounds and museum

The Gate of Death greeted prisoners at the execution courtyard that was a former shooting range. While some prisoners were hanged, most were shot by a firing squad. Some 250 to 300 people were executed at the small fortress. A museum on the fortress grounds covers the period leading up to the Occupation, the Occupation itself, and the national resistance to the Nazis.

The Gate of Death greeted prisoners at the execution courtyard that was a former shooting range. While some prisoners were hanged, most were shot by a firing squad. Some 250 to 300 people were executed at the small fortress. A museum on the fortress grounds covers the period leading up to the Occupation, the Occupation itself, and the national resistance to the Nazis.

The Ghetto Museum in the Terezin´s big fortress

The Ghetto Museum, located in the former ghetto, familiarizes tourists with the horrific daily life of prisoners. It also exhibits the artwork of children inmates. Visitors find out about the ghetto’s cultural activities and spiritual life as well as about the hunger, illness, fear of transport, and death that permeated the camp until its liberation by the Soviets on May 8, 1945. The exhibition is a memorial to the 86,934 people deported from Terezín to other locations; only 3,586 survived.

The Terezin ghetto

The 7,000 Czechs who lived in the town before the Nazis took over were expelled in June of 1942, making way for some 50,000 Jews. About 155,000 Jews were brought there during the war. Approximately 87,000 were deported to concentration camps farther East, while about 34,000 died in the ghetto. Of the more than 10,500 children who lived in the ghetto before being deported East, only 245 survived the war.

The visit of the Red Cross

Delegates of the International Red Cross visited the ghetto on June 23, 1944. In preparation for the visit, changes took place. Flower beds added color while musical and children’s pavilions were also built. More cultural activities were offered. Sick prisoners were transported to Auschwitz. The Nazis also made a propaganda film. Most of the Jews in the film were deported East and murdered several months after the visit. The Red Cross delegates were duped, not realizing it was a concentration camp.

Daily life in the Terezin ghetto

A lack of water, medicine, and toilets, the presence of insects, and infectious diseases were rampant in the ghetto. Hunger, stress from slave labor, and epidemics riddled prisoners’ lives. Housing was overcrowded with three-tiered bunks composed of beds only 65 centimeters wide. As slave labor, all ghetto inmates aged 16 to 60 had to work 52 to 54 hours per week; from November of 1944, the time spent working skyrocketed to 70 hours per week.

A lack of water, medicine, and toilets, the presence of insects, and infectious diseases were rampant in the ghetto. Hunger, stress from slave labor, and epidemics riddled prisoners’ lives. Housing was overcrowded with three-tiered bunks composed of beds only 65 centimeters wide. As slave labor, all ghetto inmates aged 16 to 60 had to work 52 to 54 hours per week; from November of 1944, the time spent working skyrocketed to 70 hours per week.

Prayer room

Attics, former garages, cellars, storage rooms, and rooms in civilian houses hosted secret prayer rooms during the Nazi regime. This particular prayer room was discovered in the early 1990s. Fifty-three-year-old Rabbi Artur Berlinger, a German-Jewish professor imprisoned in Terezín, found an empty room measuring five by four meters in a small shed in the yard of today’s 17 Dlouhá Street and transformed the space into a prayer room, bringing with him his own liturgical objects. The walls are decorated with Hebrew script, and the Star of David adorns the ceiling, though the décor has been ravaged by time. Unfortunately, the floods of 2002 washed away most of the lower wall ornamentation. Berlinger sent his two daughters to England, but he and his wife were not so lucky – they died in Auschwitz.

Family accommodation

Above the prayer room is a former accommodation typical for about two percent of the Jews, for example, those that served on the Council of Elders, the ghetto’s self-administration supervised by the Nazis. The claustrophobic space consisted of several tiny rooms and was used for about six people who slept on bunk beds.

The central morgue

Relatives could sometimes receive permission to say goodbye to their loved ones at the central morgue, which was divided into Jewish and Christian sections because about 10 percent of the Jewish inmates practiced the Christian faith. Visitors can see a cart for dead bodies and narrow, wooden coffins. Earth from various concentration camps is kept in a display case. After the body was brought to the morgue, it was sent to the crematorium, and then the wooden or paper urn was buried.

The Columbarium

The urns were originally stored at the Columbarium. Now plaques dedicated to victims of Nazi rule by towns or relatives adorn the walls. Madeleine Albright visited the space in 2012, and the tour guide said that she plans to have installed a plaque commemorating her relatives who perished at the hands of the Nazis. The plaque of Madeleine Blum, for example, states that she was deported to Auschwitz on May 5, 1945. A pink and white rose adorned the tribute.

The crematorium

In June of 1942, bodies began to be cremated in four large furnaces that could hold up to four bodies each. In the Jewish cemetery around the crematorium, there are 9,000 numbered graves, nameless as these dead could not be identified. An exhibition in the foyer of the crematorium shows original documents stating the cause of death of prisoners and displays paper urns used during and after the war. At first, urns were made of wood, but then the Nazis switched to paper ones. This is where the Nazis took the gold teeth from the dead. In 1944, the SS ordered the ashes of the deceased to be liquidated. Some 22,000 urns were thrown into the river, and another 3,000 were buried.

In June of 1942, bodies began to be cremated in four large furnaces that could hold up to four bodies each. In the Jewish cemetery around the crematorium, there are 9,000 numbered graves, nameless as these dead could not be identified. An exhibition in the foyer of the crematorium shows original documents stating the cause of death of prisoners and displays paper urns used during and after the war. At first, urns were made of wood, but then the Nazis switched to paper ones. This is where the Nazis took the gold teeth from the dead. In 1944, the SS ordered the ashes of the deceased to be liquidated. Some 22,000 urns were thrown into the river, and another 3,000 were buried.

Magdeburg Barracks

The former barracks now feature an exhibition of arts in the ghetto during World War II. Some imprisoned artists were sent to work in the drafting room, where they made charts, statistics, and illustrations to accompany reports about activities of the so-called self-administration.

Drawings of Terezin´s children

This group of about 15 to 20 artists secretly created pictures depicting the raw reality of camp life. Overcrowded housing spaces, food lines, transport lines, hearses drawn by people, masses of coffins piled up in the morgue – all these themes were featured in their pictures. The artists tried to smuggle the drawings out during the Red Cross visit, but they were arrested. In July of 1944, these artists and their families were sent to the small fortress, and very few survived. Otto Ungar, Bedřich Fritta, Petr Kien, and Leo Hass – are just a few of the artists who risked their lives in an attempt to show the outside world the horrific reality of prison life.

Literature and music in Terezin

Literary works were also created in the ghetto despite a shortage of writing implements and the threat of death. The poetry and drama written in German had a mesh of German, Jewish, and Czech characteristics and proved the last examples of Prague’s German literature, largely influenced by Austrian culture. Music was no stranger to the ghetto, either. Many concerts took place.

The Terezin theatre

Theatre in the ghetto usually consisted of cabaret or revue-type programs but also children’s performances. National Theatre stage and costume designer František Zelenka was deported to Terezín on July 13, 1943, and was very active in theatre activities there. Unfortunately, he was deported to Auschwitz on October 19, 1944, and perished during the journey.