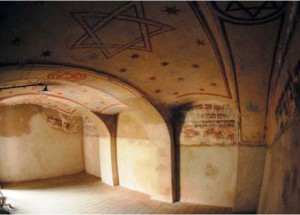

Terezin: The Prayer Room in the former Jewish Ghetto

Keeping faith in Terezín

Instrumental in giving inmates a sense of purpose and hope, the prayer room at 17 Dlouhá Street in Terezín was home to religious services tolerated by the Nazis in this town that was made into a Jewish ghetto during World War II. The five-by-four meter room was a place where prisoners could worship the teachings of the Torah and find consolation in their religious faith and strength in God. Though the décor of the space is simple and the floods of 2002 washed away the lower wall decoration, no visitor can leave this prayer room without being emotionally moved.

The history of the town

Terezín was established from 1780 to 1790 as a fortress town by Emperor Joseph II, who named it after his mother, Empress Maria Theresa. It was built to keep the Prussians out of harm’s way, but no battle was ever fought there. In the second half of the 19th century, the small fortress served as a prison. During World War I political prisoners was kept there.

Terezín was established from 1780 to 1790 as a fortress town by Emperor Joseph II, who named it after his mother, Empress Maria Theresa. It was built to keep the Prussians out of harm’s way, but no battle was ever fought there. In the second half of the 19th century, the small fortress served as a prison. During World War I political prisoners was kept there.

Terezin Concentration Camp – changes in Terezín in 1942

The 7,000 Czechs who lived in Terezín before the Nazis took over were expelled in June of 1942, making way for some 50,000 Jews. Some 155,000 Jews were brought there during the war. Approximately 87,000 were deported to concentration camps farther East, while about 34,000 died in the ghetto.

Places of worship

Empty attics such as that at 17 Dlouhá Street were often transformed into small synagogues. After the expulsion of the non-Jewish population in 1942, prayer rooms also were founded in garages, cellars, and storage spaces, for instance.

The history of the building in Terezin

Owned by František Bubák, the space served as part of a funeral parlor before World War II. Though forced to leave Terezín in 1942, Bubák reclaimed the property after the war. Because his family feared repercussions from the Communist regime, they kept the prayer room’s existence a secret while using it as a storage facility. Bubák’s descendants did not notify the authorities about it until after the 1989 Velvet Revolution that brought democracy to what was then Czechoslovakia. Visitors have been allowed to see the room since the late 1990s.

Owned by František Bubák, the space served as part of a funeral parlor before World War II. Though forced to leave Terezín in 1942, Bubák reclaimed the property after the war. Because his family feared repercussions from the Communist regime, they kept the prayer room’s existence a secret while using it as a storage facility. Bubák’s descendants did not notify the authorities about it until after the 1989 Velvet Revolution that brought democracy to what was then Czechoslovakia. Visitors have been allowed to see the room since the late 1990s.

A man with a mission: Artur (Asher) Berlinger

The man who brought the prayer room to life was Artur (Asher) Berlinger, born in Würzburg, Germany to an orthodox Jewish family on December 30, 1889. He studied at a teacher training school and fought for Germany in World War I. While residing in a Jewish community in Schweinfurt, Bavaria with his wife Berta and two daughters, Senta and Rosie, he devoted much time to religious instruction and set up a modest Jewish school with one classroom. Yet he was a man of many talents. In addition to teaching religion, he worked as a musician, music teacher, painter, calligrapher and artisan.

Kristallnacht and Dachau

Then, on November 9, 1938, the Nazis unleashed the pogrom Kristallnacht (Crystal Night) throughout Germany and parts of Austria. Broken glass littered the streets as Nazis smashed windows of Jewish-owned stores, synagogues, and Jewish schools that were destroyed with sledgehammers. Berlinger was sent to the Dachau concentration camp. Miraculously, he was released and continued his activities promoting the Jewish faith in Schweinfurt. After experiencing the horrors of Dachau, Berlinger realized that he had to protect his children from such a cruel fate, so he sent them to England.

Berlinger’s life in the Terezín Concentration Camp

Berlinger and his wife were two of the last people to be deported from the Bavarian town. They wound up in Terezín on September 21, 1942, and would spend two years there. Luck was on the Berlinger’s side on January 28, 1943. They were ordered to go to a transport but then told to return to the ghetto. In Terezín the 53-year-old Berlinger was assigned to work long hours as a craftsman in a workshop. He continued to share his faith in Judaism with others. He even designed a Jewish calendar for the 1943-44 year. Berlinger and his wife kept in written contact with their children.

The décor of the prayer room

In 1943 Berlinger happened upon the empty attic space with the vaulted ceiling at 17 Dlouhá Street. Determined to help other inmates celebrate their Jewish faith, he transformed it into a prayer room and probably used his own liturgical items during the services he led. He decorated the room himself and even painted his self-portrait as a cantor facing the wall inscription, “Know before whom you stand.” The upper walls and vaulted ceiling are decorated, but the lower wall ornamentation was destroyed during the 2002 floods. In addition to Berlinger’s self-portrait, a six-pointed Star of David is prominent. Stars of various sizes on the vaulting resemble a sky. Three burning candles are portrayed as well. Other Hebrew inscriptions on the walls that ask God for forgiveness and compassion include “May our eyes behold Your return to Zion in compassion” and “But despite all this, we have not forgotten Your name. We beg You not to forget us.” Yet another reads, “If I forget you, O Jerusalem, let my right hand forget its skill.”

In 1943 Berlinger happened upon the empty attic space with the vaulted ceiling at 17 Dlouhá Street. Determined to help other inmates celebrate their Jewish faith, he transformed it into a prayer room and probably used his own liturgical items during the services he led. He decorated the room himself and even painted his self-portrait as a cantor facing the wall inscription, “Know before whom you stand.” The upper walls and vaulted ceiling are decorated, but the lower wall ornamentation was destroyed during the 2002 floods. In addition to Berlinger’s self-portrait, a six-pointed Star of David is prominent. Stars of various sizes on the vaulting resemble a sky. Three burning candles are portrayed as well. Other Hebrew inscriptions on the walls that ask God for forgiveness and compassion include “May our eyes behold Your return to Zion in compassion” and “But despite all this, we have not forgotten Your name. We beg You not to forget us.” Yet another reads, “If I forget you, O Jerusalem, let my right hand forget its skill.”

Rosie Baum’s visit (Artur Berlinger’s daughter)

Artur Berlinger’s daughter Rosie Baum and granddaughter came back to Terezín in 2002 and visited the prayer room. She asserted that her father indeed was the author of the painted décor and Hebrew inscriptions on the ceiling and walls. According to the publication Prayer Room From The Time of the Terezín Ghetto, Rosie Baum explained, “This was the way in which my father confirmed his absolute belief in a higher authority. …He and his mother had to give up their children and all their property. The only thing that was left to them was their belief…”

Artur Berlinger’s daughter Rosie Baum and granddaughter came back to Terezín in 2002 and visited the prayer room. She asserted that her father indeed was the author of the painted décor and Hebrew inscriptions on the ceiling and walls. According to the publication Prayer Room From The Time of the Terezín Ghetto, Rosie Baum explained, “This was the way in which my father confirmed his absolute belief in a higher authority. …He and his mother had to give up their children and all their property. The only thing that was left to them was their belief…”

Death and legacy

On September 28, 1944, Artur Berlinger was sent to Auschwitz, where he perished. His wife was deported to Auschwitz on October 6 of the same year and also died there. Their daughter Senta got married and stayed in the United Kingdom. Rosie also married, though she moved to the United States. Thanks to Artur Berlinger, the prayer room played an integral role in religious activities at the Terezín concentration camp.