The Ghetto Museum in Terezín

By Tracy A. Burns

The museum’s focus

Informing visitors to Terezín about the history of the ghetto established by the Nazis in central Bohemia’s walled fortress town in November of 1941, the Ghetto Museum focuses on familiarizing tourists with the arduous and horrific daily life of prisoners. It also exhibits children’s artwork and chronicles the rise of anti-Semitism in the Protectorate of Bohemia and Moravia, established by Adolf Hitler on March 15, 1939. Visitors find out about the ghetto’s cultural activities and spiritual life as well as about the hunger, illness, fear of transport, and death that permeated the camp until its liberation by the Soviets on May 8, 1945. Recollections of survivors make up the exposition, too.

Informing visitors to Terezín about the history of the ghetto established by the Nazis in central Bohemia’s walled fortress town in November of 1941, the Ghetto Museum focuses on familiarizing tourists with the arduous and horrific daily life of prisoners. It also exhibits children’s artwork and chronicles the rise of anti-Semitism in the Protectorate of Bohemia and Moravia, established by Adolf Hitler on March 15, 1939. Visitors find out about the ghetto’s cultural activities and spiritual life as well as about the hunger, illness, fear of transport, and death that permeated the camp until its liberation by the Soviets on May 8, 1945. Recollections of survivors make up the exposition, too.

The history of the town

Terezín was established from 1780 to 1790 as a fortress town by Emperor Joseph II, who named it after his mother, Empress Maria Theresa. It was built to keep the Prussians out of harm’s way, but no battle was ever fought there. In the second half of the 19th century, the small fortress served as a prison. During World War I political prisoners was kept there.

The building housing the museum

The building housing the museum is a former school that served as a children’s home for boys from ages 10 to 15 years old during the Nazi regime and was the focal point of cultural life for youth in the ghetto. Founded in October of 1991, the museum got its current look during makeovers in 1999 and 2001.

Some gruesome statistics

The 7,000 Czechs that lived in the town before the Nazis took over were expelled in June of 1942, making way for some 50,000 Jews. Some 155,000 Jews were brought there during the war. Approximately 87,000 were deported to concentration camps farther East, while about 34,000 died in the ghetto.

The 7,000 Czechs that lived in the town before the Nazis took over were expelled in June of 1942, making way for some 50,000 Jews. Some 155,000 Jews were brought there during the war. Approximately 87,000 were deported to concentration camps farther East, while about 34,000 died in the ghetto.

Children in the ghetto

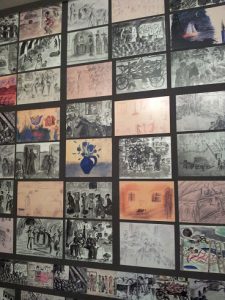

More than 10,500 children lived in the ghetto before being deported East. Only 245 survived. On the stairway of the museum, there is a large collage of children’s drawings, including pictures of boats, flowers, and nature scenes as well as dream-like and fairy tale renditions as the children celebrated their past freedom instead of focusing on the harsh reality. However, Helga Weissová-Hošková’s creations show terror-ridden everyday life in the ghetto from a child’s viewpoint. One of her drawings deals with people arriving in Terezín, dread, and fear on their faces, as the adults grip children’s hands and suitcases.

More than 10,500 children lived in the ghetto before being deported East. Only 245 survived. On the stairway of the museum, there is a large collage of children’s drawings, including pictures of boats, flowers, and nature scenes as well as dream-like and fairy tale renditions as the children celebrated their past freedom instead of focusing on the harsh reality. However, Helga Weissová-Hošková’s creations show terror-ridden everyday life in the ghetto from a child’s viewpoint. One of her drawings deals with people arriving in Terezín, dread, and fear on their faces, as the adults grip children’s hands and suitcases.

Displays depicting a cruel world

Other displays depict an even crueler world. Visitors are exposed to covers of the magazine Der Stürmer, littered with anti-Semitism propaganda. A picture in a children’s textbook shows a Jew as a poisonous mushroom. Another photo shows Hitler taking over Prague on March 15, 1939, as onlookers salute him. A sculpture is made out of suitcases that once held Jews’ belongings. A document announcing the first transport from Terezín to the East is dated January 5, 1942. An illegal radio transmitter is hidden in a suitcase to enable prisoners to get information about the war. Food vouchers for prisoners are also on display. The false identity card used by Vítěslav Lederer to escape from Auschwitz will capture visitors’ attention, too. Chilling photos remind visitors that suffering and torture were by no means limited to Terezín. One gruesome shot show victims of a mass execution in Estonia, while another depicts bodies that have been reduced to skeletons being buried in a mass grave at Bergen-Belsen.

Other displays depict an even crueler world. Visitors are exposed to covers of the magazine Der Stürmer, littered with anti-Semitism propaganda. A picture in a children’s textbook shows a Jew as a poisonous mushroom. Another photo shows Hitler taking over Prague on March 15, 1939, as onlookers salute him. A sculpture is made out of suitcases that once held Jews’ belongings. A document announcing the first transport from Terezín to the East is dated January 5, 1942. An illegal radio transmitter is hidden in a suitcase to enable prisoners to get information about the war. Food vouchers for prisoners are also on display. The false identity card used by Vítěslav Lederer to escape from Auschwitz will capture visitors’ attention, too. Chilling photos remind visitors that suffering and torture were by no means limited to Terezín. One gruesome shot show victims of a mass execution in Estonia, while another depicts bodies that have been reduced to skeletons being buried in a mass grave at Bergen-Belsen.

The visit of the Red Cross

One significant photo shows happy, smiling children during the visit of delegates of the International Red Cross on June 23, 1944. Several months later those children were deported East and murdered. In preparation for the visit, many changes had taken place in the ghetto. Flower beds added more color while musical and children’s pavilions were also built. More cultural activities were offered as well. Sick prisoners were sent to their deaths at Auschwitz. The Nazis made a propaganda film. The Red Cross delegates were fooled and approved of the ghetto, not realizing it was a concentration camp.

Daily life in the ghetto

The exhibitions give visitors a sense of the everyday turmoil and suffering that prisoners experienced. Hygiene problems, a lack of water and toilets, the presence of insects, and infectious diseases were rampant in the ghetto. Hunger, stress from slave labor, and epidemics riddled prisoners’ lives. Exhibits illustrate the overcrowded housing conditions with three-tiered bunks, each the bed 65 centimeters wide, stacked next to each other.

The exhibitions give visitors a sense of the everyday turmoil and suffering that prisoners experienced. Hygiene problems, a lack of water and toilets, the presence of insects, and infectious diseases were rampant in the ghetto. Hunger, stress from slave labor, and epidemics riddled prisoners’ lives. Exhibits illustrate the overcrowded housing conditions with three-tiered bunks, each the bed 65 centimeters wide, stacked next to each other.

Slave labor, health issues, and more

Slave labor was another fact of life in the camp. Ghetto inhabitants between the ages of 16 and 60 had to work 52 to 54 hours per week, and from November of 1944, the time spent working skyrocketed to 70 hours per week. For example, the inmates built the crematorium and railway line from Terezín to Bohušovice nad Ohří. Otto Ungar’s drawing shows the suffering and demanding work of building railway lines in 1943. The exhibition also documents the horrendous health situation. A lack of medicine and equipment plagued the camp, though the situation improved a little when medical equipment was confiscated from a Jewish doctor. Those very ill were deported East. The exposition also stresses that not only Jews inhabited the ghetto. There were many Christians as well, who were categorized as Jews by the Nazis due to their ancestry. Prayer rooms for Jews and Christians existed in basements, attics, and storage rooms.

Cultural life

Cultural activities gave prisoners a sense of self-worth and escape from the terrible conditions of their everyday lives and allowed them to rebel spiritually. Concerts, operas, cabarets, and plays were performed. Lectures took place in basements, attics, and courtyards. At the cultural exhibitions, visitors become familiarized with the costumes and scenography of František Zelenka, whose designs graced Prague’s National Theatre and the Liberated Theatre, run by the comic duo of Jan Werich and Jiří Voskovec. Zelenka died while being transported to Auschwitz in October of 1944. Posters advertising various performances are displayed, too.

Egon Redlich

Another exhibition concentrates on the life of one prisoner, Egon Redlich. Born in October of 1916, he studied law at Charles University until the Nazis closed the school down. He dreamed of emigrating to Palestine but was deported to Terezín in December of 1941. Redlich became active in planning educational activities and secret lessons for children in the ghetto. His diary, written in Czech and Hebrew, offers priceless accounts of life in the ghetto. He was deported, along with his wife and six-month-old son, on October 23, 1944, to Auschwitz, where he and his family perished.

More about the museum and other sights

The foyer of the building includes a movie theatre for documentary films, temporary exhibitions, and a model of the ghetto. Other expositions can be seen at the crematorium, the former morgue and Columbarium, the former Magdeburg barracks, and the small fortress used as a Gestapo prison, which includes a museum, exhibitions, cells, and execution grounds. Buses run regularly from Prague to Terezín, stopping near the Ghetto Museum, and the journey takes about an hour.

The foyer of the building includes a movie theatre for documentary films, temporary exhibitions, and a model of the ghetto. Other expositions can be seen at the crematorium, the former morgue and Columbarium, the former Magdeburg barracks, and the small fortress used as a Gestapo prison, which includes a museum, exhibitions, cells, and execution grounds. Buses run regularly from Prague to Terezín, stopping near the Ghetto Museum, and the journey takes about an hour.