The Small Fortress at Terezín concentration camp

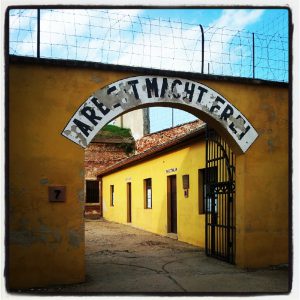

Inscribed in the capital, black lettering on a gate at the small fortress of central Bohemia’s Terezín is the Nazi slogan, “Work makes you free.” Walking through the eerie courtyards, death seems almost tangible – visitors can feel the presence of the tortured, exhausted inmates lining up for roll call, cramped in overcrowded cells or sipping soup made of bad vegetables. The Gestapo prison, neighboring the SS-controlled Jewish ghetto, was in use from 1940 to 1945. The small fortress was heavily damaged during the floods of 2002, but it has been restored to its appearance during World War II.

Inscribed in the capital, black lettering on a gate at the small fortress of central Bohemia’s Terezín is the Nazi slogan, “Work makes you free.” Walking through the eerie courtyards, death seems almost tangible – visitors can feel the presence of the tortured, exhausted inmates lining up for roll call, cramped in overcrowded cells or sipping soup made of bad vegetables. The Gestapo prison, neighboring the SS-controlled Jewish ghetto, was in use from 1940 to 1945. The small fortress was heavily damaged during the floods of 2002, but it has been restored to its appearance during World War II.

History of the small fortress before the Occupation

The small fortress existed long before it became a Nazi work camp as Terezín was easily accessible and easy to guard. Built from 1780 to 1790 and named by Emperor Joseph II after Empress Maria Theresa, it was originally intended to be a fortress that would keep the Prussians out of harm’s way. However, no battles were fought there. In the second half of the 19th century, the place also served as a prison. During World War I political prisoners were held there, including Bosnian Serb assassin Gavrilo Princip, who killed Archduke Franz Ferdinand and his wife on June 28, 1914, and was sentenced to 20 years there, though he died of tuberculosis after only a four-year stay.

The prisoners

During the work camp’s early days, mostly Czech political prisoners were kept there. The Nazis needed the small fortress because the existing prisons were full, and they were arresting many resistance fighters as well as communists. Those who aided resistance workers, people who committed sabotage, and Jews who broke anti-Semitic laws were also inmates during the initial years. After Acting Reich-Protector Reinhard Heydrich was assassinated by Czech parachutists in 1942, the Nazis imprisoned many relatives and supporters of the resistance fighters. Throughout the five years, 32,000 prisoners went through the camp and were often then deported to other camps farther East, where they met their deaths or were sent to courts or prisons. Some 3,000 of them were foreigners – from Russia, Poland, France, Britain, and other countries. Approximately 2,500 inmates died in the small fortress. A sub-camp also existed in nearby Litoměřice, where some 4,500 died due to epidemics, starvation, and forced labor in less than one year alone.

The second courtyard

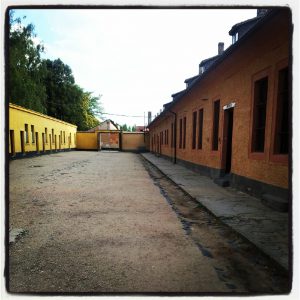

There are four prisoners’ courtyards to walk through as some of history’s darkest days seep into visitors’ souls. The second courtyard was devoted to administrative procedures, and the transports were brought there. The admission process lasted several hours as people became numbers and were often tortured. Then inmates gave up their personal belongings in the Effects Room. Each guard unit stationed in the Guards’ Room included about 110 Waffen SS soldiers. Prisoners received old Czechoslovak army uniforms in the Storage Room. Women kept their civilian attire. On the breast and back of the shirts was a yellow star if the inmate was Jewish or triangles denoting various categories. For example, political prisoners wore red triangles, and pink triangles were reserved for homosexuals. The incarcerated also received clogs, a blanket, a metal bowl, and a spoon, and all men were shaved bald.

There are four prisoners’ courtyards to walk through as some of history’s darkest days seep into visitors’ souls. The second courtyard was devoted to administrative procedures, and the transports were brought there. The admission process lasted several hours as people became numbers and were often tortured. Then inmates gave up their personal belongings in the Effects Room. Each guard unit stationed in the Guards’ Room included about 110 Waffen SS soldiers. Prisoners received old Czechoslovak army uniforms in the Storage Room. Women kept their civilian attire. On the breast and back of the shirts was a yellow star if the inmate was Jewish or triangles denoting various categories. For example, political prisoners wore red triangles, and pink triangles were reserved for homosexuals. The incarcerated also received clogs, a blanket, a metal bowl, and a spoon, and all men were shaved bald.

The first courtyard

In the first courtyard for men, roll call took place in the morning and evening. Visitors can see 17 cells. Prisoners were separated by nationality with often 60 to 90 people per cell. Wooden planks made up bunk beds that were three tiers high. Narrow shelves held personal belongings. There was one toilet and one sink, and water had to be reused. The prisoners were not allowed to use light. There was rarely any heating, and humidity tormented the inmates during the summer. Lice and insects contributed to the bad hygiene.

In the first courtyard for men, roll call took place in the morning and evening. Visitors can see 17 cells. Prisoners were separated by nationality with often 60 to 90 people per cell. Wooden planks made up bunk beds that were three tiers high. Narrow shelves held personal belongings. There was one toilet and one sink, and water had to be reused. The prisoners were not allowed to use light. There was rarely any heating, and humidity tormented the inmates during the summer. Lice and insects contributed to the bad hygiene.

Cells for Jews

While Jews were usually gathered in the adjacent ghetto, the ones who had tried to escape from the ghetto or were involved in the resistance activities were sent to the small fortress for a brutal punishment. Jews were tortured or murdered solely because of their religion. One of the two Jewish cells is a small, dark and now empty room – imagine 60 prisoners crammed together there with no toilet, no light, no fresh air, and no seating. In 1946 the brutal commander of the small fortress, Heinrich Jöckel, languished in one of these cells after being captured and sentenced to death.

The fourth courtyard

The fourth courtyard was built in 1943. Prisoners living there were forced to watch executions. The huge cells held from 400 to 600 people, who slept on the floors or in beds. There were two toilets in each cell and a glass roof added some light but made it hotter during the summer. During 1945 there were no showers in this courtyard, and typhus broke out. Up to 20 people were held in each of the 125 solitary confinement cells, which did not have toilets or seating. The third courtyard, reserved for women as of 1942, now houses exhibitions.

The fourth courtyard was built in 1943. Prisoners living there were forced to watch executions. The huge cells held from 400 to 600 people, who slept on the floors or in beds. There were two toilets in each cell and a glass roof added some light but made it hotter during the summer. During 1945 there were no showers in this courtyard, and typhus broke out. Up to 20 people were held in each of the 125 solitary confinement cells, which did not have toilets or seating. The third courtyard, reserved for women as of 1942, now houses exhibitions.

The prisoners’ diet

Overcrowded cells, a lack of hygiene, insufficient meals, and demanding labor made up a prisoner’s life. Their diet was atrocious, and portions were continually reduced. In the morning they received about 200 grams of bread and were given coffee made of grain twice a day. If they worked, they ate soup cooked with bad vegetables twice a day.

Other cells and the shower room

There are 20 solitary confinement cells. Look for cell number one. That is where Princip spent four years. During 1943 a central shower room was installed with a delousing station for clothes, where two vats or cylinders that worked on hot steam were set up. During the 10 to 12 minutes that the machines killed the insects on the clothes, up to 100 inmates were allowed to shower together. Women sometimes had hot water, but men always had cold water. Then they had to wear wet clothes, sometimes going straight to work. The longest break between showers was four months.

There are 20 solitary confinement cells. Look for cell number one. That is where Princip spent four years. During 1943 a central shower room was installed with a delousing station for clothes, where two vats or cylinders that worked on hot steam were set up. During the 10 to 12 minutes that the machines killed the insects on the clothes, up to 100 inmates were allowed to shower together. Women sometimes had hot water, but men always had cold water. Then they had to wear wet clothes, sometimes going straight to work. The longest break between showers was four months.

Sickbay and medical treatment

Sickbay, set up in 1940, initially had only eight beds. Inmates with no medical experience were assigned to act as doctors. There was also a lack of drugs and equipment. Still, some surgeries were performed. Usually, prisoners were left inside their cells when they were ill. Jewish and Russian prisoners did not receive medical treatment at all.

The former hospital and Milada Horáková

The former hospital of the small fortress, which was used only once, now contains an exhibition about Milada Horáková, a political prisoner who spent two months in solitary confinement and was executed by the Communists in 1950. Even though she was a lawyer by profession, she was selected to be a doctor at the camp. About 2,600 people died in prison from 1940 to 1945. During the last weeks of the war, spotted fever and typhoid epidemics ravaged the camp.

The one successful escape

Of the several dozen attempted escapes from the fortress, only one was successful. On Saint Nicholas Day, December 6, 1944, Josef Mattas, Miloš Ešner, and František Maršík escaped while the guards were celebrating. They climbed down a rope into the moat and through a gap in a bulwark. They hid there until the end of the war.

The execution grounds and other sites

The fortress also includes 55 kilometers of corridors, a former cinema erected in 1942 for the SS guards, and a swimming pool, constructed by Jews and students for the Nazis during 1942. The Gate of Death greeted prisoners at the execution courtyard that was a former shooting range. While a few prisoners were hanged, most were shot by a firing squad. Some 250 to 300 people were executed at the small fortress. Mass graves have been unearthed near the execution site. When K.H. Frank took control after Heydrich’s assassination, terror swept through the lands, and more executions, without trials or appeals, were carried out. A museum at the small fortress covers the period leading up to the Occupation, the Occupation itself, and the national resistance to the Nazis. There were no gas chambers at Terezín.

The fortress also includes 55 kilometers of corridors, a former cinema erected in 1942 for the SS guards, and a swimming pool, constructed by Jews and students for the Nazis during 1942. The Gate of Death greeted prisoners at the execution courtyard that was a former shooting range. While a few prisoners were hanged, most were shot by a firing squad. Some 250 to 300 people were executed at the small fortress. Mass graves have been unearthed near the execution site. When K.H. Frank took control after Heydrich’s assassination, terror swept through the lands, and more executions, without trials or appeals, were carried out. A museum at the small fortress covers the period leading up to the Occupation, the Occupation itself, and the national resistance to the Nazis. There were no gas chambers at Terezín.

Playing a significant role in the history of the Occupation

Out of the 32,000 prisoners held in the small fortress, 33 percent were sent to concentration camps while 22 percent were sent to courts. Some 17 percent were freed in Terezín, while 20 percent were released. Another eight percent died. The history of the small fortress makes up a significant part of the history of the Occupation and tells the story of the terror and inhumanity that swept through the Czech lands and Europe.

Out of the 32,000 prisoners held in the small fortress, 33 percent were sent to concentration camps while 22 percent were sent to courts. Some 17 percent were freed in Terezín, while 20 percent were released. Another eight percent died. The history of the small fortress makes up a significant part of the history of the Occupation and tells the story of the terror and inhumanity that swept through the Czech lands and Europe.