Tomáš Garrigue Masaryk: A founding father of Czechoslovakia

By Tracy A. Burns

A Czechoslovak hero

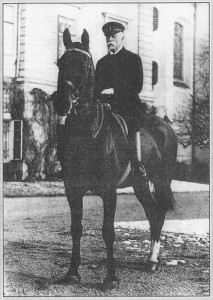

He founded Czechoslovak democracy and believed in individual responsibility. He asserted that small nations had a vital role to play in Europe and was convinced they could contribute to the world as a whole. This philosopher, scholar, and politician stressed practical ethics and exposed Czechs and Slovaks to what were then the most contemporary advancements in science, humanities, and world literature. He promoted religion as a source of morality. And he was the first president of Czechoslovakia – Tomáš Garrigue Masaryk.

He founded Czechoslovak democracy and believed in individual responsibility. He asserted that small nations had a vital role to play in Europe and was convinced they could contribute to the world as a whole. This philosopher, scholar, and politician stressed practical ethics and exposed Czechs and Slovaks to what were then the most contemporary advancements in science, humanities, and world literature. He promoted religion as a source of morality. And he was the first president of Czechoslovakia – Tomáš Garrigue Masaryk.

From March 7, 1850, to the 1880s

Born on March 7, 1850, Masaryk came into the world two years after the 1848 European revolutions, which, affecting the Czech lands, were political uprisings triggered by those with nationalistic inclinations who favored democracy and reforms in the Austro-Hungarian government. The revolutionaries were crushed, but serfdom was abolished in the Austro-Hungarian Empire. Tomáš Jan came from humble beginnings. His Slovak family was poor as his father labored as a carter and later as a steward while his German-Moravian mother toiled as a cook. Masaryk began tutoring pupils in well-off families when he was 15. The next year the eldest of three children relished his work helping the local blacksmith. Then he attended German high school in Brno, where he experienced first-hand the tension between the high-class Germans and oppressed, lower-class Czechs. Also earning his wages as a tutor, his student’s family moved to Vienna, accompanied by Masaryk. There he was exposed to the dynamic ideas of Czech students in the rather large Czech minority. He focused on philosophy at the University of Vienna. During a year’s study in Leipzig from 1877 to 1888, he met his future wife, an American from Brooklyn named Charlotte Garrigue. Masaryk married her in the USA on March 15, 1878, and took her last name as his middle name. Charlotte gave birth to five children, including her son Jan, who later became a prominent, democratic politician. Masaryk taught philosophy at the University of Vienna before transferring to Prague’s new Czech University.

A prominent writer

Masaryk was a prolific author during the 1880s and 1890s. His book analyzing the causes of suicide came out in 1881. Suicide stemmed from religious crises, he argued. After spending time in Russia from 1887 to 1888, he described the deplorable life in Tsarist Russia and the inadequacies of the Orthodox Church, citing its society’s oppressiveness and intolerance as several examples. While teaching in Prague, he established the magazine Athenaeum, featuring Czech culture as well as science. He also became involved in politics. Other books that appeared in print during this time period included Our Present Crisis in 1896. He also wrote a book about Jan Hus, the priest, philosopher, and reformer who was burned at the stake in 1415. Another work centered on Karel Havlíček, the writer, critic, politician, journalist, and publisher who was active in the 1848 revolution in the Austro-Bohemian section of the Habsburg monarchy.

The Czech Question and others

Perhaps one of his most significant works is The Czech Question from 1895. In it, he focused on the lives of young intellectuals and warned against their inclinations for radicalism and escapism. He valued and promoted their identification with the nation. The prominent writer described the foundations of democracy and how the Czech nation could contribute to Europe and to the world. He also published a series of essays concentrating on the importance of religion. Masaryk’s book The Social Question took a critical stance on Marxism. During this time he also supported the women’s movement.

The manuscript mystery and the Hilsner affair

Masaryk was not one to back down from controversy, always asserting what he believed, and never swayed by public opinion. He was involved in several scandals. He proved that the epic poems, the manuscripts of Dvůr Králové and Zelená hora, which supposedly dated from the Middle Ages and were a source of Czech nationalism, were forgeries. Czech nationalists turned against him, branding him a traitor. Then, in 1899 a Jewish vagrant named Leopold Hilsner received the death penalty for ritual murder, but Masaryk convinced the court to retry the case, arguing that the trials were anti-Semitic. Although found guilty of murdering two girls, Hilsner was given life imprisonment instead of the death penalty. The Masaryk family was the target of anti-Semitic attacks.

Wahrmund, the southern Slavs, and the Catholic Church

While Masaryk was in the Austrian Parliament called the Reichstrat, he also defended a professor from Innsbruck University, Ludwig Wahrmund, who described discrepancies between the teachings of the Roman Catholic Church and science and thus enraged the Vatican. Around this same time, Masaryk also supported southern Slavs accused of treason. Thanks to Masaryk, the government’s planted evidence containing forgeries was brought out in the open. A Protestant, he also was a severe critic of the Catholic Church’s centralism and promoted reforms. Later, as president, he would also have rifts with the Church.

From World War I to November 14, 1918

While Masaryk had fought for reforms within Austro-Hungary before the war, during World War I, he became an advocate for independence rather than autonomy. Heading the government-in-exile, he gathered Western support for Czechoslovakia. His colleague Eduard Beneš also greatly contributed to the cause as did Slovak scholar and astronomer Milan Rastislav Štefánik. Masaryk also taught Slavonic Studies at King’s College in London during the war. One of his major accomplishments concerned setting up the Czechoslovak Legions fighting in Russia against the Habsburg Empire as a segment of the French army. During a trip to the USA, he convinced President Woodrow Wilson of the need for Czechoslovak independence, and the country was created on October 28, 1918. Masaryk was elected its first president on November 14 of that year.

While Masaryk had fought for reforms within Austro-Hungary before the war, during World War I, he became an advocate for independence rather than autonomy. Heading the government-in-exile, he gathered Western support for Czechoslovakia. His colleague Eduard Beneš also greatly contributed to the cause as did Slovak scholar and astronomer Milan Rastislav Štefánik. Masaryk also taught Slavonic Studies at King’s College in London during the war. One of his major accomplishments concerned setting up the Czechoslovak Legions fighting in Russia against the Habsburg Empire as a segment of the French army. During a trip to the USA, he convinced President Woodrow Wilson of the need for Czechoslovak independence, and the country was created on October 28, 1918. Masaryk was elected its first president on November 14 of that year.

The first presidential term: prosperity and problems

While Masaryk led the country, Beneš served as Foreign Minister, leader of the Agrarian Party Antonín Švehla as Prime Minister, and Alois Rašín as Minister of Finance, though he was assassinated in 1923. The coalition parties formed the Pětka, meaning “five,” and their leaders met informally to discuss political problems. The country was a democracy considering all citizens equal and giving minorities rights to keep their national identity. There was freedom of the press and universal suffrage. Democratic elections were held. Yet in a country of 10 million inhabitants comprising six nationalities, there were bound to be problems. Masaryk took great pains to ease the Czech-German tension, and German political parties played a part in Czechoslovak governments from 1926 to 1938. Besides the Czech-German dilemma, the Slovak Roman Catholic Church and Slovak separatism caused difficulties. Since the Austro-Hungarian Empire had existed from the 16th century, Masaryk also had to deal with a lack of democratic tradition.

The second presidential term: a flourishing country and personal tragedy

Having accrued many admirers and staying in contact with commoners, Masaryk was reelected president in 1920. The country flourished with a solid, democratic base and a strong currency. It thrived economically. Yet Masaryk experienced tough times when his wife, on whom the war had taken a physical toll, died in 1923. That did not stop him from publishing, though. The Making of a State from 1925 described his experiences during World War I. He became close friends with writer Karel Čapek, and his meetings with Čapek from 1928 to 1935 led to the book President Masaryk Tells His Story, in which the president discusses his memories and philosophy.

The third presidential term: the 10th anniversary and hostile political ideologies

Masaryk received a two-thirds majority vote for his third presidential term in 1927. The year 1928 marked the 10th anniversary of the country and its democratic ideals, and these were prosperous days in Czechoslovakia, though an Austrian mentality had not been fully erased. In 1930 Masaryk turned 80, and soon trends of Communism, Fascism and Nazism invaded the land as Adolf Hitler became the German dictator in 1933.

Masaryk received a two-thirds majority vote for his third presidential term in 1927. The year 1928 marked the 10th anniversary of the country and its democratic ideals, and these were prosperous days in Czechoslovakia, though an Austrian mentality had not been fully erased. In 1930 Masaryk turned 80, and soon trends of Communism, Fascism and Nazism invaded the land as Adolf Hitler became the German dictator in 1933.

The fourth presidential term: resignation

In 1934 Masaryk was elected for a third term. Yet this time he lost his battle with health problems. He resigned in December of 1935, ending a 17-year presidential career. Beneš succeeded him as president while Masaryk spent the rest of his days at his beloved chateau in Lány, near Prague. On the night of September 1 and September 2, 1937, he suffered a stroke. Masaryk passed away on September 14.

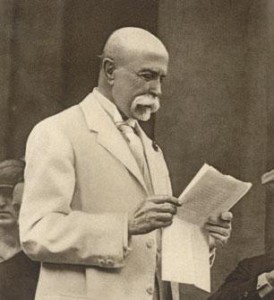

A city in mourning

In Prague, a city in mourning, black flags fluttered from downtown buildings. Busts and pictures of Masaryk with that distinctive, fluffy, white mustache dotted the town and covered the front pages of numerous newspapers. Black banners reading “TGM” adorned Saint Vitus Cathedral and buildings on Wenceslas Square. Thousands of soldiers and legionnaires marched in his funeral procession on September 21 as 146 military standards made an appearance. Draped with the Czechoslovak flag, his coffin was carried on a gun carriage through the city. On its last leg to Lány, the coffin traveled by train, placed in a car covered in wreaths and flowers.